This imaginary conversation took place at the Peace and Justice Association at Marquette University October 10, 2009.

Bob Graf

St. Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Society of Jesus, asks us to use the five senses of our imagination to pray. Mahatma Gandhi, the father of India, asks us to look within to find God. Today I am asking each of you to listen to this imaginary conversation between St. Ignatius of Loyola and Mahatma Gandhi on nonviolence and sustainability.

First, I will ask each imaginary character to summarize his autobiography with a view toward the topics of nonviolence and sustainability. Then I will ask them to have a “spiritual conversation”, as St. Ignatius liked to call it, on nonviolence and sustainability.

St. Ignatius of Loyola

Hello, my name is Ignatius. I was born in 1491 in the Basque country of Spain. As I describe myself in the first line of my autobiography (where I use the third person): “Up to his twenty-sixth year he was a man given to the vanities of the world, and took a special delight in the exercise of arms, with a great and vain desire of winning glory.” 1 I might add I was also quite the ladies man, although the Jesuits do not like admitting to that fact.

A turning point in my life came when a cannon ball hit my legs in a battle. After the battle, the enemy French soldiers took me home to a castle at Loyola to recuperate. During a long and painful recovery I had plenty of time to read and think. I asked for some popular tales of chivalry and romance to read but there were none in the castle. So they gave me the “Life of Christ” and a book on the Lives of the Saints to read.

I noticed that whenever I fantasized about the glorious deeds I would do as a soldier I felt happy. But after that fantasy left me I felt somewhat down and discouraged. On the other hand, I observed that when I thought of the great deeds of Jesus and the saints, like Dominic and Francis of Assisi, I felt a deep sense of peace and energy that was lasting. I was born a Roman Catholic and remained one, but I had a change of heart and realized that only by doing God’s will, being a follower of the way of Jesus, would I be satisfied and find true peace.

After my convalescence, I decided to go on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land to seek direction in what I should do with my life. The first stop on the pilgrimage was the shrine of the Black Madonna in the monastery at Montserrat. After a general confession that took three days and praying all night before the statue of Mary, I left my arms, my sword and dagger at the altar in the Church. I exchanged my fine clothes with a beggar and began my pilgrimage. I had been a military soldier and now I was a soldier of Christ.

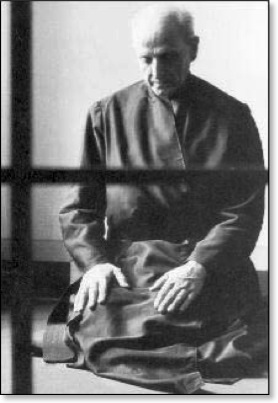

My first stop was in nearby Manresa, Spain. I meant to make it brief but ending up staying there a year. I abstained from wine, except on Sundays, and ate no meat. I begged alms every day for myself and for others in need. Since I had been so vain about my looks, I let my hair go wild and did not cut my nails. I worked in the hospital with diseased persons that others did not want to touch. I lived in a cave and spent much of my time in prayer. These were times of great consolations and visions for me and yet times of deep depression and desolation. I had a bad case of scruples — in today’s vernacular one might say I was manic depressive or bipolar. However, during this time I started to write down my thoughts and insights into what would later become The Spiritual Exercises. 2 It was here that I clearly saw my mission in life which was “to help souls” 3, or as you may put it today, to be of service to all, especially the poor, the weak and the marginalized.

I finally made it to the Holy Land overwhelmed with enthusiasm; but, due to the political situation, the religious authorities made me return home. Back in Spain I started to give my “spiritual exercises” to others who were seeking to more closely be followers of Jesus. I was jailed by the Inquisition’s religious authorities on a couple of occasions for helping souls because I had no formal education in theology and philosophy. Each time I was imprisoned, I did not hire a lawyer or fight it. I felt I was more learned in spiritual exercises than my judges but knew that I did not have the academic foundation to rest on. Therefore I decided to make my way to Paris to study theology and philosophy after my last release from jail. On the way there and in Paris, I continued to attract others who desired to learn the ways of the heart in the Spiritual Exercises.

I continued to get in trouble with Church authorities while in Paris and eventually a group of us, including Peter Farve and Francis Xavier, decided to take vows together. Shortly after Peter Farve became a priest in July of 1534, our group of six lay people and one priest, on August 15th, bound ourselves together by a vow to go to Jerusalem where we would spend the rest of our lives for the good of souls. If we failed, our backup plan was to offer ourselves to the Holy Father to be employed in whatever ministries he thought best for us, to be in service to the church.

We made our way to Venice where we intended to take a ship to Palestine. While waiting, we worked in a hospital with the very sick, especially with victims of syphilis. A few of my companions went to Rome to seek permission of the Pope for our pilgrimage to the Holy Land, but I did not go since a few persons in the Papal court thought I was a heretic. To our surprise, the Pope gave us permission for our pilgrimage, money for the journey and said that the six of us who were lay people could be ordained by any bishop of our choice.

After our ordination it became clear that we could not, because of the political situation, go to the Holy Land. Therefore we dispersed to various Italian cities and became “street preachers.” If someone asked, we said we were “The Company of Jesus.”

Eventually, I and two companions went to Rome to pursue our alternative plan to serve the Holy Father. In a small town on the outskirts of Rome, La Storta, I experienced a profound vision. It was a vision of Jesus carrying the cross, with God the Father at his side. Jesus said “I wish you to serve us” and the Father added “I will be propitious to you in Rome.” 4 I was placed at the side of Jesus by the cross.

As it happened, all went well for us in Rome, and we became the Society of Jesus; we were missioned by the Holy Father to promote the faith and the word of God by preaching, educating and offering The Spiritual Exercises. We were also asked “to show ourselves ready to reconcile the estranged, compassionately assist and serve those who are in prisons or hospitals and, indeed, to perform any other works of charity, according to what would seem expedient for the glory of God and the common good.” 5

My autobiography ends here with this statement that with the help of my companions some works of piety were founded in Rome such as the house of catechumens to teach our faith, the house of Santa Maria — a home for ex-prostitutes — and the establishment of an orphanage. 6 The rest of the story has been told my many.

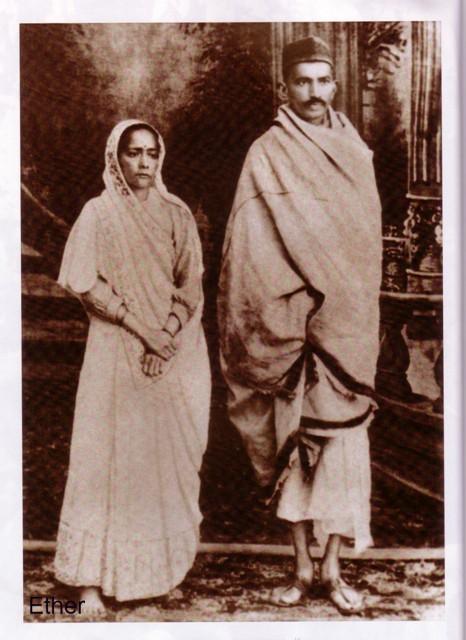

Mahatma Gandhi

I wrote my autobiography when I was 47 years old, calling it The Story of my Experiments with Truth. 7 I was born in 1869 to a middle class devout Hindu family in India. Compassion, vegetarianism, fasting for self-purification, and mutual tolerance between individuals of different creeds were present in my early life, but like you, Ignatius, I had not made them my own.

As was the custom of the region in India where I lived; I entered into an arranged child marriage when I was 13 years old. “We didn’t know much about marriage, for us it meant only wearing new clothes, eating sweets and playing with relatives.” However, our first son was born when I was 15 and although he lived only a few days, we had four more sons. Our marriage, like my understanding of God, grew with age and wisdom.

Although I was an average student in school, my family really wanted me to be a barrister or lawyer. So in 1888, less than a month shy of my 19th birthday, I left my family and traveled to London, England to study law at University College and to train as a barrister. However, before I left, my mother made me take a solemn vow to observe the Hindu precepts of abstinence from meat, alcohol and promiscuity. This vow played an important role for me, for although I experimented with English customs, even taking dancing lessons, it was this vow that pushed me to explore rich traditions like vegetarianism and Christianity as well as my own Hindu religion.

My attempts at establishing a law practice in Mumbai and in my home town of Rajkot were a failure, after arriving back in India in 1891. Finally, after offending a British officer by my rude behavior, I was forced, in order to support my wife and family, to take a job with an Indian firm in South Africa.

In South Africa, although successful as barrister, I faced overt acts of racial discrimination and prejudice, being an Indian. These acts helped me to understand two things: that service to the poor was my heart’s desire and the need to question the Indians’ relationship to the British Empire. What was supposed to be brief turned into a three year stay where I helped, unsuccessfully, to fight a bill outlawing Indians from voting in South Africa; I also successfully helped to organize the Natal Indian Congress in 1894, an organization that molded the Indian community of South Africa into a homogeneous political force.

I returned home to India in 1896 to fetch my wife and children and return to my work in South Africa. Returning to South Africa with my wife and family I was attacked in Durban by a mob of white settlers and escaped only through the efforts of the wife of the local police superintendent. However, I refused to press charges against any member of the mob, since one of my principles was not to seek redress for a personal wrong in a court of law.

During this period, 1893–1914, I spent mostly in South Africa working to serve others, especially the poor and those in the Indian civil rights movement I developed through my experiences some of the key concepts that were to guide me the rest of my life. It was during this time, at the age of 38, I took the vow of “brahmacharya.” This is a Hindu vow where one devotes oneself to a lifestyle of purity of heart. It involves celibacy, fasting and a detachment of thought, word and deed, much like the vows taken by religious, such as the Jesuits, in the west.

In the Indian civil rights movement in South Africa, we became determined to practice an active type of nonviolence or love. Ahimsa is the word we used. When we were looking for a word to describe the Indian civil rights movement and struggle in South Africa we had a contest in the paper “Indian Opinion.” From this contest we came up with the word “Satyagraha”, describing our struggle to hold on to the truth and the power it brings to us. In our struggle, using satyagraha or the power of creative nonviolence to defy unjust laws through civil disobedience, we obtained some civil rights for the Indian people of South Africa.

During this time in South Africa, I remained loyal to the British Empire, participating in both the Boor War and the Zulu Rebellion as an ambulance driver. At the time I still believed the British Empire would free us.

These experiences and the reading of John Ruskin led me to the concept of “Sarvodaya”, the Welfare of All, as a guiding principle of my way of life. The first ashram was formed in South Africa, a disciplined community where the common good — welfare of all — was the rule.

When we returned to India in 1915, I found my life moving in the same direction, continuing my experiment with truth. My reputation as a human rights leader had preceded me and I found myself as a leader in the independence movement.

Soon we founded an Ashram community, calling it the “Satyagraha Ashram” and immediately we were tested when an “untouchable” family applied for membership. Our community had no problem accepting the family, but the larger community did. Soon our funds started drying up. I kept my trust in God and a stranger came by one day with a major donation.

My life in India became involved in a number of struggles for truth, satyagraha. One of the struggles was to abolish the indentured labor system; another one was for the rights of farmers in the indigo business in Champaran region. Another struggle in Kheda was against oppressive taxation by the British at a time of famine. Non-cooperation, non-violence and peaceful resistance were our “weapons”. In our struggle we were imprisoned, rejected and insulted, but the truth did prevail.

However, there continued to be violence on both sides of the struggle for independence and civil rights. Built on the idea of “swara,” 8 self government or self reliance, we responded with a movement of non-cooperation which included the “swadeshi policy” — the boycott of foreign-made goods, especially British goods. Linked to this was the advocacy that “khadi” (homespun cloth) be worn by all Indians instead of British-made textiles. This struggle of becoming self reliant and independent, with this national boycott, lasted two years. When this movement turned toward violence, I called it off but was still tried by the British government, found guilty of sedition, and sentenced to six years in prison. My frequent trips to prison gave me the time to write much of this autobiography which ends in 1931. I ask you the reader or listener “to join with me in prayer to the God of Truth that God may grant me the boon of Ahimsa, nonviolence in mind, word and deed.”

Bob

From the summary of your autobiographies, it seems like you two have a lot in common. Since you come from different times and quite different cultures, this similarity is remarkable. For our conversation on nonviolence and sustainability I have given each of you a copy of each other’s autobiography and a few books and articles of the other’s writing. I would like to start the conversation with each of you defining what you mean by the word nonviolence in today’s terms, and then have you talk about this and each other’s words and deeds relative to nonviolence.

Gandhi

For this discussion my definition of nonviolence is that it is “the soul-force or the power of Godhead within us.” 9 “It is positive state of love, doing good even to the evil–doer.” 10 Nonviolence or Ahimsa is a weapon of the strong. It calls forth the “greatest courage.” The word we coined to express our application of nonviolence in the movement is Satyagraha. It is the constant seeking of Truth and holding on to this truth force. We vindicate the truth not by “inflicting suffering on the opponent but one’s self.” 11 Allow me to give a contemporary example in word and in deed of nonviolence. Judith Brown in her book about me gives a definition of my Satyagraha or what you may call “creative nonviolence” as “striving nonviolently to the point of sacrifice rather than fighting to attain one’s vision of truth.” I believe Professor Duffy of Marquette gave you, Bob, that quote as one of his favorite definitions.

Bob Yes he did.

Gandhi

An example in deed of nonviolence was given by one of my disciples, Martin Luther King Jr., here in America, when he was in jail in Birmingham for an act of civil disobedience. In a letter, he talks about how “disciplined nonviolence totally confused the rulers of the South.” They did not know what to do. “When they finally reached for clubs, dogs and guns, they found the world was watching, and then the power of nonviolent protest became manifest.”

Ignatius

As you know, Gandhi, in my time, in the sixteenth century, we did not have a word for what you call nonviolence. However, reading your writings and listening to you today, I am reminded of a central theme of the Spiritual Exercise, my guidelines to find God in all things. Ever since I surrendered my weapons of war and became a “soldier of Christ” I had a deep desire to be with Jesus “in accepting all wrongs and all rejections and all poverty, both actual and spiritual.” 12

For me, “seeking the Truth meant to be humble,” 13. The greatest humility for me was to want the truth of Jesus’ life to be fully the truth of my own. I saw two standards we could follow: the standard of the world, riches, honor and pride, or the standards of Jesus, poverty, insults and rejection. However like you, Gandhi, my truth or soul force was not passive. I actively encouraged my followers to pursue the truth, not with the violence that surrounded my times and contemporary world but with the disciplined courage to act in love that expresses itself in deeds more than words.

Although I did oppose dueling and forms of retaliation, I do not think you can consider me a person of nonviolence. I lived in times when religion was taken seriously and we Catholics, Protestants and Muslims each thought our religion was the true one and had no problem using violence to defeat each other.

Gandhi

Ignatius you are too humble. I know you lived in violent times and supported violence against other religions, but you did not let this violence enter into your work or that of the Society of Jesus. Besides supporting Britain in the Boor War and Zulu rebellion, as I previously mentioned, I supported Britain and Indian involvement in World War I. I regret this but, as with your support of war, they were learning experiences on my pilgrimage to nonviolence.

Your work on The Spiritual Exercises is saturated throughout with nonviolence. In the beginning of the exercises, The First Principle and Foundation, you state how all creation is a gift of God’s love and our response is to use all things to deepen God’s life in us and to return this love to God. You constantly talk about the discipline that is needed to be free and detached to use the power of God’s love in your guidelines in the spiritual exercises. Ignatius, you spend much time and thought on being aware and discerning God’s will, essential elements of nonviolence. You have already mentioned your main message of humility, following the standards of Jesus over the standards of the world. You ask your companions not to fear rejection and insults in seeking the Truth. You ask God to place you on the cross of Jesus, the greatest symbol on nonviolence in the western world. And how can I ignore The Contemplation to Attain Love at the end of the Exercises. You seek to find God’s love, the power of nonviolence, and in all things to express our love in deeds more than words. Ignatius, if I had known more persons like you, who lived the message of Jesus rather than just talked it, I might have become a Christian myself.

Ignatius

Gandhi, I am glad you stayed a Hindu, since the universal concept of God and love you express has helped me, members of my Society of Jesus and countless Christians to understand and appreciate the unity we possess, being brothers and sisters in God. Now let’s move on to sustainability. We both claim to be men whose message is explained in deeds over our words, but we both certainly use lots of words.

Sustainability is another word we did not have in my times, but I believe I understand the concept of creating and maintaining something that endures through time. I tried to instill in my companions through my words, the Spiritual Exercises, the Constitutions of the Society and my own example, a deep awareness that God can be found in all creation, that any experience probed to its depth reveals God.

Jesuits are the largest missionary order in the Catholic Church. They are taught not to impose Christianity and their culture on others, although some have, but to bring Christianity forth from the local culture and faith. A recent General or Leader of the Society of Jesus, Father Pedro Arrupe used the modern word “inculturation” to describe this way of proceeding. Father Arrupe who was from Spain but was formed by his experiences in the East, said “inculturation” is the incarnation of the Christian life in local culture and transforming the culture into a new creation, not imposing anything on it. 14

Fr. Pedro Arupe S.J.Is not this spirit of “inculturation” at the heart of sustainability? Now, I must admit, this way of proceeding has gotten the Order in lots of trouble with the Roman Catholic Church over the years. From the Jesuit Reductions in South America, sustainable compounds for natives, through the Jesuit mission in China and to the modern-day proponents of Liberation Theology in Latin America, this principle has been controversial. The Jesuits were even suppressed for a time but were renewed and revived. This paradox of the Society, loyal to the Church and Holy Father but often at odds with the Church, continues today.

Another way of proceeding that breeds sustainability in the Society of Jesus is by encouraging persons to discern God’s will in how to serve the Church and do the most good to help souls, especially the poor and marginalized. I wanted my members to do their best in their ministries and to work in such a way that they could move on to other work, knowing that the work they started would continue. Like a pilgrim, I wanted members to forever be seeking to be like Jesus, to give all and be willing to surrender everything even unto death, and to bear the message of new life and to help souls. However, Gandhi, I talk too much about a subject you know more about.

Gandhi

I am not so sure about that, but the principles of sustainability were at the heart of the nonviolence in our struggle for independence in India. The word related to sustainability we used was Swadeshi, the use and service of our immediate surroundings over those more remote or foreign. In economic terms it is the insistence on the use of local goods made by local communities and in one’s own country, and preferably hand-made or home grown.

It is why you frequently see me pictured at a spinning wheel, making Khadi, hand-woven and hand spun cloth. These locally made products and others were key to securing our independence from England.

I would urge that the doctrine of Swadeshi is the only doctrine consistent with the law of humility and love, something you can appreciate, Ignatius. It is arrogant to think of launching out to serve the whole world or even one’s country when one can hardly even serve one’s own family and friends. Swadeshi applies to all aspects of life. How can we stop wars in foreign lands when we teach war in our own schools?

In the 1970’s rural farmers, the majority in India, were ruined by the so called ‘Green movement’ brought to my country by the USA. American Agri-businesses came to my country and told farmers if they abandoned the traditional way of farming and used the fertilizers, chemicals, insecticides, genetic seeds and such they could grow and produce more. In the short term they did, but before long they found themselves in ruin, damaging the environment and themselves. They became dependent on these outside businesses. The rate of suicide among farmers skyrocketed.

Now there is a growing movement in my country of rural institutes, people producing the clothing, energy and food they need in a very sustainable way and teaching others this sustainable way of life. Bob, you saw on the Pilgrimage to India walking in my footsteps, sustainable villages or ashrams or institutes living a lifestyle of Swadeshi.

But I must admit that in India as in the USA many look at making Kahdi or growing your own food or eating and buying locally as hindrances to independence, not the key to it. God forgive us that the first Wal-Mart store, under the name Best Price, was just opened this summer in India.

People misunderstood my teachings suggesting I was against technology. I was not. All I was trying to do was to establish how you use something, like technology, which is just as important as your goal for using it. As Jesuits would say, Ignatius, “the end does not justify the means.”

However, I have a deep hope and have been inspired by things like the sustainable rural institutes of my followers in India and with economic justice leaders like Vandana Shiva and Will Allen, showing others how to Grow Renewable Affordable Food.

As you noted in your previous comments, Ignatius, nonviolence and sustainability, in whatever words or forms we express it, is at the heart of who we are and the power of God within. I suggest we close our conversation with a prayer you wrote at the end of the Spiritual Exercises that expresses our desires to surrender ourselves to the will of God.

Take, Lord, and receive all my liberty,

my memory, my understanding,

and my entire will,

All I have and call my own.

You have given all to me.

To you, Lord, I return it.

Everything is yours; do with it what you will.

Give me only your love and your grace,

that is enough for me. 15

Bob Thank you!

Bibliography

Arrupe S.J., Pedro, One Jesuit’s Spiritual Journey, The Institute of Jesuit Resources, 1986

The Constitutions of the Society of Jesus and Their Complimentary Norms, The Institute of Jesuit Resources,1996

Fleming S.J., David, What is Ignatian Spirituality, Loyola University Press, 2008

Fleming S.J., David, Draw Me Into Your Friendship, The Spiritual Exercises, The Institute of Jesuit Resources.1996

Gandhi, M.K., The Selected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Vol. V, The Voice of Truth, Navajivan Trust, 1968

Gandhi, M.K, Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule, Navajivan Trust, 1938

Gandhi, M.K, An Autobiography or The Story of My Experiments with Truth, Navajivan Trust, 1927

Ignatius of Loyola, St. Ignatius Own Story as told to Luis Gonzalez de Carmara, Loyola University Press, 1980

O’Malley, John, The First Jesuits, Harvard University Press, 1993