« Jon Higgenbotham | | Michael Cullen »

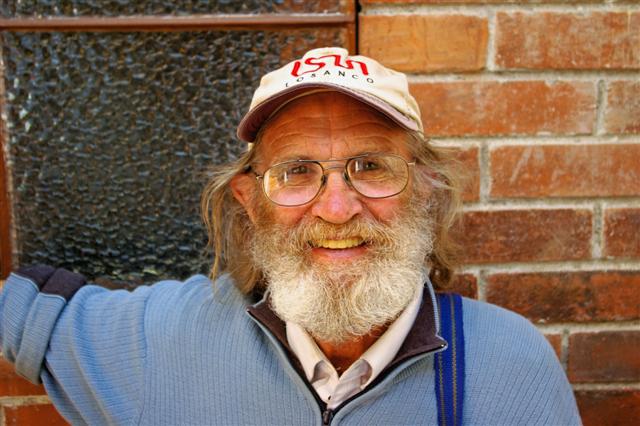

Lorenzo (Larry) Rosebaugh, 1968 and Today RIP

Read:

Listen:

Interview with Larry Rosebaugh on Chicago Public Radio, Worldview, with host Jerome McDonnell, Dec. 22, 2006

1968: From the Milwaukee 14 Statement at the time of the action

Fr. Larry Rosebaugh, 33, a member of the religious community of Oblates of Mary Immaculate, is on the staff of Casa Maria House of Hospitality in Milwaukee and has worked as a longshoreman on the Milwaukee docks. After serving a year as a parish priest in St. Paul, he taught religious for three years in Duluth and spent a year in the inner-city of Chicago.

2006: Lorenzo Rosebaugh Autobiography

Lorenzo was an Oblate priest serving the poor and marginalized in Guatemala City, Guatemala. His Memoir To Wisdom Through Failure is his journey through life that led him to prison, Brazil, El Salvador, Mexico and to live in Guatemala and be with the poorest of the poor. It is a story of compassion, resistance and hope. Lorenzo truly learned the “language of the poor”. You can order this book through Epica Press by using the form attached to the page To Wisdom Through Failure.

Lorezeno Rosebaugh In Guatemala

Lorezeno Rosebaugh In El Salvator

Book Review

(Published in the New York Catholic Worker paper. March-April issue)

To Wisdom Through Failure:

A journey of Compassion, Resistance And Hope

by Larry Rosebaugh, OMI

EPICA Washington, DC, 2006

Reviewed by Karl Meyer

Even before I read this book, I already believed that Larry is one of the truest disciples of Jesus that I have known. He literally hitchhikes his way into the lives and hearts of the poorest in Brazil, Mexico, El Salvador and Guatemala, experiencing in his own person the beauty and joys, the horrors and the hopes that are real in their lives. I’ve known Larry for thirty nine years, mostly through the annual letters he writes from places where he lives prayerfully and joyfully and painfully among the poor. He seems to read the Gospel ideas of Jesus and say, “This is meant for me.”

In fifty years with the Catholic Worker and other justice movements, I’ve known a multitude of the finest people of our time. But Padre Lorenzo Rosebaugh has plunged deeper and longer than most into the life of “the least of these, my brothers and sisters,” and accompanied them in the most sensitive way. If you want to figure out how to live the Gospel in our particular age, you will be stirred deeply by reading this autobiographical book.

When I met him in 1968, he seemed a nice conventional priest, an Oblate of Mary Immaculate (OMI) dressed in a black suit with Roman collar and teaching at St. Benedict High School in Chicago. He moved in and took care of my house of hospitality, St. Stephen’s House, for a few months at a time of crisis and transition for my family. After a summer there, he moved on to Casa Maria Catholic Worker in Milwaukee, and this is where the story picks up steam of a unique passion, as his OMI superior tells him. “You are free to go there since you see this as…identifying with the most abandoned and oppressed and trying to be a voice for the voiceless.”

Casa Maria was a place of dynamic passion in those years, with the leadership of Mike and Nettie Cullen. Within a couple of months Larry is drawn into the Milwaukee 14 action, publicly burning 1-A draft files taken in a nonviolent raid at the Milwaukee Federal Building. He is thirty three years old. In a photograph of the action he is still clean-cut, in a Roman Collar, but this will not last long. The draft board action leads to twenty-two months in jails and prisons, including ten months in the “hole” at Waupun State Prison for resisting the unreasonable rules of the slave labor regimen.

A year Later

It had been a quiet week in the summer of ‘71 at the Sandstone, Minnesota Federal Prison clinic where I was a prisoner and working as a so-called physiotherapist. We were looking out the barred windows onto the spacious lawn of the prison grounds, when we saw a raggedy bearded man, in a white t-shirt and khaki pants (similar to our uniform jail clothing) walking casually up the long road to the front entrance. Fellow inmates joked that he must be coming back voluntarily from a “truck parole,” because he couldn’t make it on the outside. A “truck parole” occurs when an inmate trustee makes his escape in a prison-owned truck.

Within minutes, the prison loudspeaker boomed out, “Karl Meyer, report to the chaplain’s office.” The raggedy pilgrim was Larry, allowed a surprise visit by his brother OMI priest , the chaplain, who limited the visit to a half-hour. There could not have been a greater contrast between Larry and the official prison chaplain, with his big ring of keys, his salary and benefits, his trailer home where he lived alone, and his passionate hobby of hunting ducks with his Labrador retriever.

When we next hear from Padre Lorenzo, he is living on the streets among the poorest of the poor in Recife, Brazil.The story deepens, the plot thickens, like the soup of salvaged vegetables that he brews each day on an open fire to share with his brothers and sisters on the street. After beautiful and awful experiences, he is arrested by brutal police, falsely accused of stealing the vegetable cart used to collect food, jailed in unspeakable conditions, beaten and brutalized by inmate thugs who run the cell in which he is housed. Missed by fellow OMIs in the Recife mission, he is finally located and released through the intercession of Dom Helder Camara, the saintly Archbishop of Recife. Then friends arrange an interview to tell his story to First Lady, Roslyn Carter, who is visiting Brazil. After six years in Brazil, he was felled by Hepatitis.

He spends several years as a Catholic Worker pilgrim in the United States, with a year in federal prison for going over the fence at the Pantex nuclear weapons assembly plant in Amarillo, Texas and later another fifteen months in prison for climbing a tree at Fort Benning Georgia with Father Roy Bourgeois and Linda Ventimiglia to broadcast the last appeal of Archbishop Oscar Romero to Salvadoran soldiers in training for counter insurgency warfare at the School of the Americas.

Can we stop now? No! By 1984 we find him working with Kathy and Phil Dahl-Bredine in a barrio of a small town in Chihuahua, Mexico. In 1986 he begins six years of accompaniment and priestly service among Salvadoran campesinos, returning to their fields after years as refugees from the terror and civil war of the 1980′s in El Salvador.

After a half year of recovery and renewal in the States, he is off again for seven years of parish ministry among indigenous tribal people in the mountains of northern Guatemala, communities still suffering from the effects of civil war there. The stories from his experience become even more compelling.

In 2000 at the age of sixty five, he returns to the US to care for his aging mother. Along the way he pulls together this book, saying near to the end of it, “After being back in the United States over two years I feel sort of like a fish out of water having been exposed to the poor and their living conditions, I anxiously await the day I can return to Guatemala.”

As I write this, Padre Lorenzo is again immersed in Guatemala and through the help of our friend Mary Lou Pedersen, I receive again his powerful Christmas letters.

In the words of T.S. Eliot’s “Four Quarters,” “The hint half guessed, the gift half understood is incarnation.” In the end, Lorenzo succeeds at two things at least, to be a true human being, and even to be a true Christian.