Gordon Zahn (1923–2007)

Obituary for Gordon Zahn

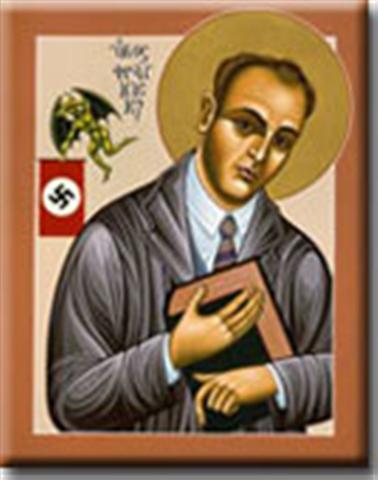

Franz Jägerstätter Martyr for Peace

Blessed Franz

JägerstätterGordon Zahn, a local resident of Milwaukee, was responsible for letting the world know about Franz Jägerstätter, an Austrian conscientious objector who was beheaded by the German military for his refusal to cooperate with the Nazi war effort. At the time of his death, Franz and his wife Franziska Jägerstätter, a faithful partner in his terrible sacrifice and a witness to peace herself, had three daughters under the age of six. Franziska suffered many years of economic punishment, discrimination and social exclusion before Austrian attitudes to her husband’s conscientious objection began to change.

The change occurred in the early 60’s when Gordon Zahn, peace activist and sociologist at Boston University, came to her little town. She showed Gordon the letters that Franz wrote from prison and his willingness to give all, despite the pleas of local townspeople, family and priest, for his belief in the principle of nonviolence.

Gordon wrote a book about Franz Jägerstätter called In Solitary Witness: The Life and Death of Franz Jägerstätter. The world began to learn about this man of conscience, an example for our times. Just last week the Roman Catholic Church declared him “Blessed” and a Martyr for Peace.

Gordon Zahn was born in Milwaukee in 1918 and graduated from Riverside High School. He, himself, was a conscientious objector to World War II and spent time in a CO camp out east. He went on to become a famous sociologist and peace activist, friend to Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton and many other great peace figures of his time. With others he was a co-founder of the Catholic Peace Fellowship and Pax Christi. Some years ago, after retirement from Boston University, he returned to Milwaukee, his home.

I first visited Gordon when he went to live in St. Camillus. since he was suffering from Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson’s disease causes dementia, and with each visit I saw that his memory, starting with recent events, had faded. The computer he wrote with was removed from his room, and eventually he could not remember his own writings, like In Solitary Witness. It was during this time I read the book and tried to remind him about it. There was a glimmer of recognition.

He had some old friends at the time who regularly would visit him along with others he had known in the past. The last public appearance I remember was when his friends and I arranged for him to accept a peace award at a Mass at Gesu parish, where I was working at the time.

In his last years he was moved to the dementia ward of St. Camillus, where people with severe cases of Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia live. He lost his ability to remember words. He became difficult to understand, and it was difficult to know if he understood you or not.

I went to see him in June 07 to tell him of the great news, as perhaps others had, of the beatification of Franz Jägerstätter. I found him at the lunch table sleeping in his wheel chair. His companion at the table, who was quite clear-minded for this area, told me that Gordon spent most of his time, day and night, sleeping. She suggested that I yell in his right ear to awaken him to my presence. I chose, rather, to sit and wait. I told him about Franz, and the lady at the table and a nurse’s aide nearby were very interested. After a while the nurse’s aid came by, and speaking loudly in his ear, told him I was there. He asked for my name. We gave it to him (not that he could remember me). While he was awake I told him again about Franz, but am not sure how much he understood. The nurse had held up his juice glass and gave him a drink. He said something like “that is good”. She left him with instructions to drink the rest of it.

I think he wanted more but could not hold the glass, so I started to slowly give him the rest of the juice. He drank it all, was appreciative in his own silent way, and went back to sleep. He looked good for his age, 89, and I had my camera present to take his picture but I did not. It was one of those holy moments, when I was in the presence of one saint who brought our awareness to another saint of peace.

We are blessed to have had Franz Jägerstätter, the conscientious objector, as a model to follow today, and doubly-blessed by having had Gordon Zahn as one of us, a Milwaukee person of peace.

Further reading about Franz Jägerstätter

Here are some other sites and articles to read about Franz Jägerstätter and his beatification by the Catholic Church.

Franz Jagerstatter: Letters and Writings from Prison-Book Review

Franz Jägerstätter: A hard history to face. The Tablet (London) / 20 October 2007

Tribute to Gordon Zahn by Catholic Peace Fellowship

Date Set for Beatification of Franz Jägerstätter by the Catholic Churcgh

John Dear S.J., a Jesuit peace activist, wrote an article called “Franz Jägerstätter’s Refusal”, which can be found under “articles” on his site at: http://www.johndear.org/

Press Notice of Pax Christi

4th June 2007

Franz Jägerstätter to become Martyr for Peace

It is with great joy that we hear of the plans for the beatification of Franz Jägerstätter, the Austrian farmer who was beheaded in Brandenburg, Germany, on 9th August 1943, for refusing to fight in Hitler’s army. (Announcement from Congregation for the Causes of Saints, 1 June 2007) His cause has been long promoted by Pax Christi.

Speaking of the beatification, Bishop Malcolm McMahon, President of Pax Christi said: “The extraordinary courage of Franz Jägerstätter, a faithful Catholic, has been an inspiration to many and a powerful witness to peace and nonviolence. In an age of war and violence we urgently need the example of those who use their consciences to make judgements about what is evil - and refuse to take part in it. The recognition of this man’s holiness by the Church should encourage us all to stand up for peace, justice and human dignity.”

Franz believed that he would be committing a sin if he acted against his conscience and agreed to fight for the National Socialist state. For him, this was a situation in which he had to obey God more than the commands of secular rulers. In following the commandment ‘you shall love your neighbour as yourself’ Franz decided that he could not fight with weapons of war. For refusing to undertake military service he was sentenced to death in Berlin and was beheaded in Brandenburg on 9th August 1943.

Pax Christi offers a warm message of support to his widow, Fransiska Jägerstätter, a faithful partner in his terrible sacrifice and a witness to peace herself. Their three daughters were all under the age of six at the time of his death. Franziska suffered many years of economic punishment, discrimination and social exclusion before Austrian attitudes to her husband’s conscientious objection began to change. He is now honoured as a hero in Austria. Franziska still serves the small village church in St Radegund, Upper Austria, where Franz himself was sacristan. We rejoice with her and her family.

Pax Christi commemorates the anniversary of Franz Jägerstätter with an ecumenical service in London each year, and has organised several pilgrimages to St Radegund since the first British Pax Christi group went there in 1975.

For more information on Franz Jägerstätter:

Contact Pax Christi on 0208 203 4884 or 0208 340 6639 or go to our website

http://www.paxchristi.org.uk/PeacePeople.html

From the Catholic Peace Fellowship

http://www.catholicpeacefellowship.org/index.asp

June 6, 2007

Pope Approves Objector for Beatification

We rejoice! The Church has granted official recognition to Franz Jägerstätter, a Catholic conscientious objector from Hitler’s army, as a martyr for the faith, thus clearing the way for his beatification and eventual canonization. On June 1, Pope Benedict XVI approved a series of decrees, issued by the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, that attributed martyrdom to Jägerstätter, a husband and father of three who was beheaded on August 9, 1943, for refusing any collaboration with the Nazis. In our March visit to the Vatican, the Catholic Peace Fellowship was informed by Monsignor Robert Sarno of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints that this step was forthcoming. We were asked to wait for the official pronouncement, which came last Friday.

A declaration of martyrdom enables a “Servant of God” to be beatified, or declared “Blessed” by the Church. For those who are not martyrs, proof of a miracle is required. Those with the title Blessed, according to Sarno, are worthy of both imitation and veneration by the faithful. All that remains for Jägerstätter to receive this title is for his home diocese of Linz, Austria, to set a date for the beatification liturgy. The next step after beatification is canonization - official recognition by the Church that this person is a Saint. Proof of a miracle received through the intercession of the beatified, subsequent to beatification, is needed for canonization. This requirement applies to all, including martyrs (those who have died for the faith) and confessors (those who have been persecuted and have suffered for the faith).

The Catholic Peace Fellowship has long held up Jägerstätter as an example of a Catholic whose conscience forbade him to participate in war (see “In Light of Eternity: Franz Jägerstätter, Martyr,” published by the CPF Staff in 2003). This young man, despite a wild and rebellious youth, in his adulthood became a devout Catholic, a third-order Franciscan, and a church sexton for his local parish. Jägerstätter read and prayed over the Scriptures and the lives of the Saints, and his conscience was shaped and formed by his active participation in the sacramental life of the Church. He understood that he was a part of the Kingdom of God and that, as a Catholic, his allegiance was to his “Eternal Homeland” - not to “the Fatherland.” Although advised by his parish priest and local bishop that his duty was to serve his country and preserve his own life for the sake of his family, Jägerstätter held firm to his belief that to cooperate with the Nazis was to cooperate with evil, and so refused to join the military.

Franz Jägerstätter was a conscientious objector, one whom we look to, and now can pray to, for guidance. When confronted by skeptics on the issue of Christians and conscientious objection, we at CPF are often asked the following question: “What if all of the American Christians had become conscientious objectors during World War II?” We can now respond with even more confidence: “What if all the German Christians, like Jägerstätter, had become conscientious objectors?” We are a universal Church, not just an American Church. Hitler was only able to oversee the massive slaughter of six million Jews and others because ordinary people, most of whom were Christians, obeyed men rather than God. The witness of Franz Jägerstätter reminds us of our duty of noncooperation with evil, and the crucial role that conscientious objection plays in the lives of the faithful. We rejoice that Franz Jägerstätter will soon be called Blessed, and hope that this recognition will encourage Catholics in every country to look more deeply into where their allegiances lie. We recall the words of Father Jochmann, the chaplain to Jägerstätter while he was in prison: “I can say with certainty that this simple man is the only saint I have ever met in my lifetime.”

Let us pray the Prayer for the Beatification of Franz Jägerstätter:

Lord Jesus Christ, You filled your servant Franz Jägerstätter with a deep love for you, his family and all people. During a time of contempt for God and humankind you bestowed on him unerring discernment and integrity. In faith, he followed his conscience, and said a decisive NO to national socialism and unjust war. Thus he sacrificed his life. We pray that you may glorify your servant Franz, so that many people may be encouraged by him and grow in love for you and all people. May his example shine out in our time, and may you grant all people the strength to stand up for justice, peace and human dignity. For yours is the glory and honour with the Father and the Holy Spirit now and forever. Amen. (Diocese of Linz, Austria).

In Peace,the CPF Staff

Whispers in the Loggia http://whispersintheloggia.blogspot.com/2007/06/blessed-objector.htmlFriday, June 01, 2007

The Blessed Objector

In his morning appointments, the Pope received Cardinal Jose Saraiva Martins CMF, prefect of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints.

Departing from the usual Vatican practice of a semipublic consistory for the declarations of causes, the Holy See announced that, during the prefect’s audience, Pope Benedict “authorized the Congregation” to publish his green-light for two causes for canonization, a whopping 327 beatifications and seven instances of “heroic virtue,” the “venerable” whose causes require miracles before they may proceed.

While among the new Blessed are to be found 127 martyrs of the Spanish Civil War and 188 from 17th century missionary efforts in Japan, the day’s standout declaration is that of the martyrdom of Franz Jägerstätter, an Austrian whose conscientious objection to the Nazi draft led to his beheading in 1943, aged 36.

As the grip of the Third Reich tightened in the late ‘30s and early ‘40s, Jägerstätter lived as a husband and farmer and served — after, so it’s said, a “wild youth” — as a parish sexton in rural Austria; his widow, Franziska, is still alive at 94. After he was ordered to join the German army in early 1943, despite pressure which reportedly came even from the ecclesiastical authorities, he refused, was promptly jailed, and killed at Berlin within six months.

Jägerstätter has long been an icon of the peace and non-violence movements — in the Vietnam era, his witness was upheld by no less than the brothers Berrigan, Thomas Merton and Dorothy Day. However, today’s declaration from the Holy See ends a years-long push for his cause to be declared a martyrdom by Rome, thus paving the way for his beatification without a miracle.

Two takes on Jägerstätter — first, from Robert Royal of the Faith & Reason Institute:

Jägerstätter received only a basic education at the local school, but he developed good reading and writing skills. When in his mature years he became an ardent believer, he would take time out of his demanding work on the farm to read the Bible and spiritual works. By the time he was imprisoned, he was well versed enough in Christian history and thought that this “simple farmer” was delighted to find a copy of St. John Chrysostom’s sermons among the prison books….

[B]y 1936 Jägerstätter was a firm and active believer and began serving as the sexton in the local church. Around that year, he wrote to his godchild with the boldness of spiritual expression that was characteristic of him: “I can say from my own experience how painful life often is when one lives as a halfway Christian; it is more like vegetating than living.” And he poignantly adds: “Since the death of Christ, almost every century has seen the persecution of Christians; there have always been heroes and martyrs who gave their lives — often in horrible ways — for Christ and their faith. If we hope to reach our goal some day, then we, too, must became heroes of the faith.”

In the meantime, he went about his business, much like others, but with important differences. He had three children and a farm to run, but Jägerstätter did not use family needs as an excuse to deviate in the slightest from what was right. He stopped going to taverns, not because he was a teetotaler, but because he got into fights over Nazism. At the same time, he practiced charity to the poor in the village, though he was only a little better than poor himself. The usual custom in the village was to give a donation to the church sexton for his help in arranging funerals and prayer services. Jägerstätter refused them, preferring to join with the faithful rather than act as a paid official. The period of self-discipline prepared him for much more demanding sacrifices.

When the Nazis arrived, not only did he refuse collaboration with their evil intentions, he even rejected benefits from the regime in areas that had nothing to do with its racial hatreds or pagan warmongering. It must have hurt for a poor father of three to turn down the money to which he was entitled through a Nazi family assistance program. But that is what he did. And the farmer paid the price of discipleship when — after a storm destroyed crops — he would not take the emergency aid offered by the government.

As the Nazis organized Austria, Jägerstätter had to decide whether to allow himself to be drafted by the German army and thus collaborate with Nazism. Two seemingly good reasons were given to him, sometimes by spiritual advisers, why he should not resist. First, he was told, he had to consider his family. The other argument was that he had a responsibility to obey legitimate authorities. The political authorities were the ones liable to judgment for their decisions, not ordinary citizens. Jägerstätter rejected both arguments. In normal times, of course, obedience to authority may be required even when we disagree on certain policies. But the 1940s in Austria were not normal times: to obey for obedience’s sake would have been to do what Adolf Eichmann would later plead in his trial in Jerusalem — he was just following orders.

The consequences of Jägerstätter’s position were obvious: “Everyone tells me, of course, that I should not do what I am doing because of the danger of death. I believe it is better to sacrifice one’s life right away than to place oneself in the grave danger of committing sin and then dying.” But he serenely decided that he could not allow himself to contribute to a regime that was immoral and anti-Catholic. Jägerstätter was sent to the prison in Linz-an-der-Donau, where Hitler and Eichmann had lived as children. According to the prison chaplain, 38 men were executed there, some for desertion, others for resistance similar to Jägerstätter’s (no others have been positively identified). His Way of the Cross would not be long. In May, he was transferred to a prison in Berlin. His parish priest, his wife and his lawyer all tried to change his mind. But it was useless. On Aug. 9, 1943, he accepted execution, even though he knew it would make no earthly difference to the Nazi death machine.

A Father Jochmann was the prison chaplain in Berlin and spent some time with Jägerstätter that day. He reports that the prisoner was calm and uncomplaining. He refused any religious material, even a New Testament, because, he said, “I am completely bound in inner union with the Lord, and any reading would only interrupt my communication with my God.” Very few men could have made such a statement without seeming to be in denial or utterly mad. Father Jochmann later said of him: “I can say with certainty that this simple man is the only saint I have ever met in my lifetime.”

…and from Jesuit Fr John Dear, recounting a visit with the martyr’s widow for the National Catholic Reporter:

Death, terrible and certain. And early. With what strength did he face it? For starters he had come to the same conclusion as Gandhi, that non-cooperation with evil is as much a duty as cooperation with good. “It is still possible for us, even today, to lift ourselves, with God’s help, out of the mire in which we are stuck and win eternal happiness — if only we make a sincere effort and bring all our strength to the task. It is never too late to save ourselves and perhaps some other soul for Christ.”

And he imbibed the spirit of nonviolence. “As a Christian, I prefer to do my fighting with the Word of God and not with arms,” he wrote. “We need no rifles or pistols for our battle, but instead spiritual weapons — and the foremost among these is prayer.”

The night Franz died, a chaplain paid him a visit. Said Franz: “I am completely bound in inner union with the Lord.” The chaplain later testified: “Franz lived as a saint and died a hero.”

I once made a pilgrimage to St. Radegund. It was in 1997, during my tertianship year, on my way to Northern Ireland. I wanted to pray at Franz’s grave. I bore an invitation to the Jägerstätter house, but finding the place posed a problem. I was by myself, and didn’t speak German. I trudged through the village for hours, magnificent farmland on all sides, but no landmark or signpost pointed the way. Finally I came upon an elderly lady in her yard eating plums off a tree. “Can you tell me where the Jägerstätters live?” She smiled. “I’m Frau Jägerstätter.”

She looks like Georgia O’Keefe, has the sparkling eyes of Mother Teresa, a warm, gentle soul with an infectious joy and loving kindness. She carries herself with humility, a hint of shyness. But beneath lies strength, a solid faith, deep peace, towering Gospel conviction. She stands, to my mind, as much a saint as her martyred husband. After Franz died, she took up his job as sacristan and set about to raise their three girls and keep his memory alive.

She offered words of welcome and showed me around. Our first stop, the old family home, where Franz lived and worked, now a national museum. I ambled through the rooms and gazed upon the displays. I examined Franz’s letters and his belongings, while Franziska and one of her daughters offered commentary, bringing Franz alive. During the evening Franziska opened her photo albums and we gathered around, and the family conjured precious memories, warm and worn, story upon story.

I was on sacred ground — and me with no gift to offer in return, but one. I told Franziska that their story had influenced me long ago to become a priest, had goaded me into activism against nuclear weapons and war And I said Franz has become a kind of icon. The Catholic peace movement holds his memory aloft. His witness has passed into timelessness and come to inspire the likes of Thomas Merton, Dorothy Day and Daniel Berrigan. Franziska glowed. Most of this was news to her.

Did you ever imagine it? I asked. That one day you would meet the pope? That you would inspire the faith of people around the world? That your home would achieve the dignity of a national museum? That pilgrims like me would flock to visit you? That Franz would be proposed for canonization?

Question after question; the poor woman could scarcely keep up. “Never,” she answered. The Nazis had dispatched him with German finality. “I thought no one would ever know about him. I hid his letters under my mattress for decades. Then, in the early 1960s, Gordon Zahn learned of him and wrote his book, In Solitary Witness, and that started the whole thing.”

My last morning there we shared a liturgy in the village chapel. We prayed in German and English for our families and friends, for the church and the world. And we prayed for the abolition of nuclear weapons and war. After Eucharist, we stood in silence by Franz’s humble grave.

It lies along the outside wall of the small chapel where he attended daily Mass. Above it stands a typical Austrian crucifix bearing the words of Matthew’s Gospel: “Whoever wishes to save his life must lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it.” It was one of the most moving spiritual and liturgical experiences of my life. As I bid farewell, Franziska pressed into my arms a bag of plums and apples from her yard, and some homemade bread.

Some months ago, the Vatican informed Franziska that its commission had approved Franz’s beatification. Now we’re all awaiting the official Vatican announcement and the date.

To my mind, this is an astonishing turn of events. In his time, church officials had heaped ridicule upon Franz’s insistence that Jesus forbids us to kill. Now this turnabout, a kind of judgment against the “devout” German and Austrian Catholics who cheered the war and fought for Hitler. But more than that, the turnabout is a sign. It’s a sign that points to the nature of sanctity, a sign of the future of sanctity.

In a world of total war, a world on the brink of destruction, only one kind of sanctity bears fruit — the one that Jesus embodied and Franz embraced. Daring nonviolence that refuses to kill no matter the pretext. Willingness to die without a trace of retaliation. Divine, universal love for everyone, even the enemy. And public, prophetic, outspoken defiance of patriotic militarism and state violence.

In an insane world, Franz points the way: refuse to fight, refuse to kill, refuse to be complicit in warmaking, refuse to compromise — and pit your very self against structures of violence with all the nonviolence in your soul.

Jägerstätter is the second Nazi-era resister to be beatified by Benedict XVI; in the fall of 2005, the German-born pontiff beatified Cardinal Clemens August von Galen (1878–1946), the “Lion of Munster” whose residence was firebombed in light of his outspokenness against the regime. Von Galen died less than a week after returning from Rome and the reception of his red hat.

Rocco Palmo, Philadelphia, PA, VA

Rocco Palmo writes from America for The Tablet, the international Catholic weekly published in London. He also authors “Almost Holy,” a fortnightly column for Busted Halo, an online magazine on spirituality and culture run by the Paulist Fathers. Palmo’s appeared as a commentator on things Catholic in The New York Times, Associated Press, The San Francisco Chronicle, BBC, National Public Radio, The Washington Post and Religion News Service, among other print and broadcast outlets. A Philadelphia native, Rocco Palmo attended the University of Pennsylvania, from which he earned the Bachelor of Arts in Political Science.