Father At War

Reflections of a father with a son in Iraq by Francis Pauc

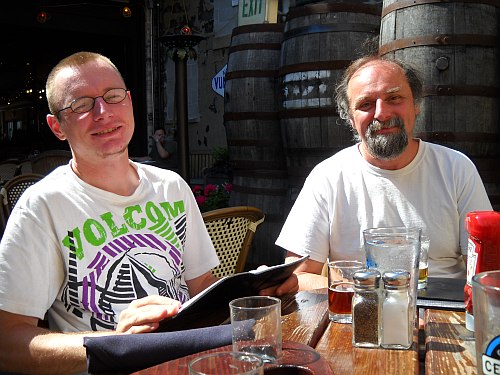

Father & sonFrancis Pauc is a graduate of West Point, Class of 1980. He served as an officer for six years after receiving his commission, five of those as a helicopter pilot. He had a gradual change of heart that started after he met his wife in Germany, and became a pacifist. Now, despite his best intentions, his oldest son is in the Army and deployed to the Middle East. His youngest son is graduating high school and will also join the military.

These letters, and other articles that he has have written over the years are his efforts to work for peace in a violent world. Thus far, he feels he has been very unsuccessful. His own flesh and blood is following the path that he rejected. This hurts him a lot. He says: “It would be easy for me to say, ‘Screw it’, and stop trying. I won’t stop. I will keep writing and speaking out, because it needs to be done.”

Stopping a Round

“Yeah, I took a round to the chest once.” “What?”

It is not often, during the course of casual conversation, that somebody mentions that they got shot. But then, it isn’t often that we get a chance to talk with Hans. Karin and I were with Hans at my brother’s house. My brother, John, is Hans’ godfather, and the two of them are close. They share an interest in guns, so the conversation veered that direction while we were visiting. At one point, the discussion turned to body armor, and that was when Hans told us that he had been hit in Iraq. Hans’ description of the incident was very matter-of-fact. He could have just as well have said, “Yeah, I bought a pizza last night.” Hans went on with his story.

“Some farmer shot at me with a 7.62 round. The armor stopped it, but I got knocked down on my back. I got up again and started firing. Everybody else fired at him too. We brought that farmer’s clay house down around his head.”

Hans’ aunt heard Hans’ story and she asked him,”Why was the farmer shooting at you?”

Hans replied,”I don’t know. All I know is that he was shooting at me.That’s all that matters.”

A good question and good answer, depending on your perspective. An observer of the event would definitely be interested in why there was all this shooting. An active participant in the firefight would have no such interest. Hans was only concerned with surviving and the “why” of the situation was irrelevant to him. It still is.

Hans has only told me a very small fraction of what happened in Iraq. I was teasing him once about him hanging around the VFW and letting the old guys buy him beers. Hans told me to my face that he can tell those old guys things that he can never tell me. They were in combat, and I never was. Hans told me that those guys ‘get it”, but I can’t. Hans wasn’t criticizing me, he was simply stating a fact. My experience in the military was radically different from what Hans endured, and I really can’t understand what happened to him. He’s right in that regard.

I went to the grocery store with Hans. There was a man there who looked like he could have been from the Middle East. Hans tensed up, and he began to tell me how hard it was for him to be around people of “that ethnicity”. He told me that he couldn’t be with people who looked like the ones who tried to kill him a few years ago. Hans’ comments were blatantly racist, but…they were also understandable to me.

I get the impression from Hans that he and his comrades regarded the Iraqis with indifference bordering on contempt. I’m sure that the Iraqis returned the favor. Hans endured trauma at the hands of some of the Iraqis. He also inflicted violence on them. His lasting aversion to people who look like they are from the Middle East is at a gut level. It is pointless for me to talk about it with my son, because he has been hurt in a deep place where words and logic never go. Something inside of Hans is scarred, and he hasn’t healed. On one level, Hans knows that his feelings are irrational, but they are also terribly real. Perhaps his attitude is there to keep him safe. He has been hurt, and now he avoids the people that remind him of that hurt.

It is often hard for fathers and sons to relate to each other. I think that Hans’ wartime experiences have made our relationship even more difficult. There is barrier between us now that wasn’t there before he went to Iraq. It’s an invisible wall that is almost always there. Sometimes the wall dissolves briefly, like when we went to shoot Hans’ pistol at the range, or when we sat on the front porch while Hans burned a Pall Mall. Most of the time the wall is there, silent and impenetrable.

I wish that I could Hans in my arms, like when he was little boy. I wish that I could make the monsters go away. I can’t.

Have a good Memorial Day.

Frank

Finding the Exit

We haven’t seen Hans since July. He calls frequently. Often the calls are about money; more specifically, his lack of money. He does occasionally call just to talk. He tells us about his work. Hans seems bored and restless. He has no interest in re-enlisting. The thrill is gone.

After having spent three years in the Army, Hans has realized that things are not what like he thought they would be. The Army keeps sending him to schools to get him eligible for promotion to sergeant, but the truth is that Hans really isn’t interested in becoming a sergeant. Obviously, he would like the pay increase that goes along with a promotion, but Hans sees what the NCO’s ( non-commissioned officers ) do for a living, and it doesn’t appeal to him. Hans joined the Army to drive tanks and blow things up, to put it bluntly. He enlisted to do things that were exciting. Sergeants don’t necessarily do exciting things. Sergeants train people, they write reports, they inspect equipment, they order supplies. Hans looks at a future in the Army as being progressively duller and less active. He’s probably right.

When Hans talked about his prospects in the Army, it reminded me of a conversation I had with my company commander in Germany back in 1984. I remember that I was in the break room in the barracks with Major Rose. He was trying to fix an ancient television set, and we started talking while he was attempting to resurrect this device. I told him how much I liked flying Blackhawks, and how I really did not want to get stuck in a desk job. Major Rose stopped his repair work for a moment and looked at me. He was a thoughtful man, and he patiently tried to explain to me that, as I rose in the ranks as an officer, I would get less and less flight time. I would become more of a manager, and less of a hands-on leader and a line pilot. My reaction was similar to Hans’ feelings. I liked flying and I liked being a platoon leader. Why couldn’t I just stay where I was, doing what I was doing?

The Army doesn’t want people to stay where they are. The Army wants people to be in constant competition with their peers. The military uses an “up or out” philosophy. A soldier either moves up in the ranks, or he is forced out. Competition is fundamental to the military culture. It’s all about winning or losing. It has to be that way, because in war losing can mean death. It is true that other institutions have cut-throat ways of selecting their leaders, but the military has made competition a way of life.

Hans is pondering what he wants to do in a life outside of the Army. That is difficult to do because the military is all-consuming. The Army doesn’t give a soldier time to consider the future; there are too many things happening in the present to allow for that. As his departure date approaches, Hans will have to look more closely at his options. It is often hard for a soldier to even imagine civilian life while he or she is still enmeshed in a military culture. I did not know how it felt to be out of the Army until I was actually out.

Hans still wants the adrenalin rush. The Army provides that. There are many petty and mindless activities in the Army, but they are tolerable because interspersed within the boring routine are moments of sheer terror. It cannot be denied that people do exciting things while they are in the military. I flew helicopters at 140 knots at treetop level, and Hans drove Abram tanks across sand dunes at 60 mph. Even in peacetime, things get crazy, and that is why a person puts up with all the rules and regulation. There is always an element of danger involved in the profession, and that, by itself, is attractive.

Hans won’t get a desk job or work in a factory unless he absolutely must. He is thinking mostly now about working on an oil rig in the Gulf. He talked to me about pirates that roam the Gulf of Mexico. I was blissfully unaware that such people existed. Hans assured me that there really are pirates, and they don’t wear funny hats or say, “Arr, Matey.” I’ll take his word it. I actually think that Hans likes the idea because it gives him a reason to carry a 9mm Beretta. He still wants an adventure. I hope he finds one.

Iraq War: Forever changed our lives

Letter to Editor of Milwaukee Journal Sentinel published March 20, 2013

Tuesday, March 19th, is the tenth anniversary of the U.S. invasion of Iraq. The total monetary cost of the war is well in excess of a trillion dollars. Over four thousand American troops died in the conflict, along with hundreds of thousands of Iraqis.

After all of this expenditure of lives and treasure, Iraq is no more secure, and no less violent than it was before we invaded the country to take down Saddam Hussein. Our country is not any better off either.

Although the statistics about the war are impressive, they are also somehow distant and impersonal. For most people in the U.S. the war has always seemed far away and not quite real.

It is not that way for our family. Our son went to war in Iraq. He was in combat there, and he killed a person. He came home a different man. When Hans came back to us after a year, I looked into the eyes of a stranger. The boy we knew is gone, and he is never coming back.

For us the Iraq war is very real and very personal. We have not suffered nearly as much as other people have. However, the war has forever changed our lives.

Finding the Exit

We haven’t seen Hans since July. He calls frequently. Often the calls are about money; more specifically, his lack of money. He does occasionally call just to talk. He tells us about his work. Hans seems bored and restless. He has no interest in re-enlisting. The thrill is gone.

After having spent three years in the Army, Hans has realized that things are not what like he thought they would be. The Army keeps sending him to schools to get him eligible for promotion to sergeant, but the truth is that Hans really isn’t interested in becoming a sergeant. Obviously, he would like the pay increase that goes along with a promotion, but Hans sees what the NCO’s ( non-commissioned officers ) do for a living, and it doesn’t appeal to him. Hans joined the Army to drive tanks and blow things up, to put it bluntly. He enlisted to do things that were exciting. Sergeants don’t necessarily do exciting things. Sergeants train people, they write reports, they inspect equipment, they order supplies. Hans looks at a future in the Army as being progressively duller and less active. He’s probably right.

When Hans talked about his prospects in the Army, it reminded me of a conversation I had with my company commander in Germany back in 1984. I remember that I was in the break room in the barracks with Major Rose. He was trying to fix an ancient television set, and we started talking while he was attempting to resurrect this device. I told him how much I liked flying Blackhawks, and how I really did not want to get stuck in a desk job. Major Rose stopped his repair work for a moment and looked at me. He was a thoughtful man, and he patiently tried to explain to me that, as I rose in the ranks as an officer, I would get less and less flight time. I would become more of a manager, and less of a hands-on leader and a line pilot. My reaction was similar to Hans’ feelings. I liked flying and I liked being a platoon leader. Why couldn’t I just stay where I was, doing what I was doing?

The Army doesn’t want people to stay where they are. The Army wants people to be in constant competition with their peers. The military uses an “up or out” philosophy. A soldier either moves up in the ranks, or he is forced out. Competition is fundamental to the military culture. It’s all about winning or losing. It has to be that way, because in war losing can mean death. It is true that other institutions have cut-throat ways of selecting their leaders, but the military has made competition a way of life.

Hans is pondering what he wants to do in a life outside of the Army. That is difficult to do because the military is all-consuming. The Army doesn’t give a soldier time to consider the future; there are too many things happening in the present to allow for that. As his departure date approaches, Hans will have to look more closely at his options. It is often hard for a soldier to even imagine civilian life while he or she is still enmeshed in a military culture. I did not know how it felt to be out of the Army until I was actually out.

Hans still wants the adrenalin rush. The Army provides that. There are many petty and mindless activities in the Army, but they are tolerable because interspersed within the boring routine are moments of sheer terror. It cannot be denied that people do exciting things while they are in the military. I flew helicopters at 140 knots at treetop level, and Hans drove Abram tanks across sand dunes at 60 mph. Even in peacetime, things get crazy, and that is why a person puts up with all the rules and regulation. There is always an element of danger involved in the profession, and that, by itself, is attractive.

Hans won’t get a desk job or work in a factory unless he absolutely must. He is thinking mostly now about working on an oil rig in the Gulf. He talked to me about pirates that roam the Gulf of Mexico. I was blissfully unaware that such people existed. Hans assured me that there really are pirates, and they don’t wear funny hats or say, “Arr, Matey.” I’ll take his word it. I actually think that Hans likes the idea because it gives him a reason to carry a 9mm Beretta. He still wants an adventure. I hope he finds one.

Which is the Better Path?

Yesterday, Peace Action sponsored a rally at the Milwaukee County Courthouse to mark the 11th anniversary of the American war in Afghanistan. I planned on attending the rally. It seemed important to me to join others to speak out against an apparently endless, useless, and mostly forgotten war on the other side of the world. Our son, Hans, killed a man during combat in Iraq, so I am very aware of the damage that our wars cause, and ending these wars is both a personal and political issue for me.

I didn’t go to the rally. Something else came up. Mohamed, a young man who emigrated here from Tunisia, called me to set up a time when we could meet and study Arabic together. Mohamed has been teaching me Arabic for the last few months, and it is difficult for us to synchronize our schedules. The only time that worked for Mohamed was exactly the same time that rally was being held. I decided to spend the time with him.

I spent about an hour with Mohamed, talking and drinking coffee at Culver’s. We did work on some Arabic grammar, but we also took time to just talk. Mohamed told me about his very pregnant wife, and about their continuing efforts to buy a house. He told me about going to the noon prayer at the mosque ( he met me right after that service was completed ). I told him about my struggles with our grown up kids. I told him about how my wife, Karin, teaches religious education to little kids at our church. He told me about what was taught to the Muslim kids. Mohamed told me about what it was like to grow up in Tunisia when it was still a police state. That reminded of a story about my wife’s uncle, who was a soldier in the German Army during the Nazi regime. Before we knew it, our time was up and we each had to move on to other pressing matters.

I am sure that everyone that attended the Afghanistan rally was trying to work for peace. I have been to numerous demonstrations over the years, and I know how they generally run. The purpose of a rally is to wake people up. It is an attempt to point out an injustice and to galvanize people into action. There is great value in this. At rallies there are lots of signs and speeches and shouting from the rooftops ( maybe not in a literal sense ). I have also noticed that there is usually not a lot of listening on anybody’s part. A rally is not designed to promote a discussion; it is designed to ram home a message.

Did I work for peace by spending an hour in a restaurant with Mohamed? We barely mentioned any of the wars and chaos that curse our world. We hardly even thought about politics. We talked mostly about mundane things; the kinds of things that concern most every father or husband. We talked about our faiths, our families, and Arabic grammar. In many ways it could be considered a rather boring conversation. However, over the course of several months and many such conversations, Mohamed and I have established a relationship. He is no longer just a young man trying to teach some old guy a new language. Mohamed is now my friend, and I hope that I am that to him too.

Mohamed and I often disagree, but we can speak honestly to each other. I talk to him partly because I want to understand Arab culture and the Muslim religion. More importantly, I want to know Mohamed as Mohamed. I want to know him as person like myself, who has similar fears and hopes. I want to be part of his world, and I hope he will be part of mine.

How do we create peace in this world? Do we make heroic efforts to end wars and strife? Do we make small attempts to reach out and touch others, and then try to build trust on an individual level? Should we do both?

Lessons Learned from Hans Part 2

I tend to over analyze things, and to look for meaning under the surface of things. Sometimes that tendency gets me into trouble, but in my discussions with Hans it was often necessary in order for me to understand him. Hans uses words sparingly, and his answers to my questions were sometimes evasive. I have drawn some conclusions from very limited information, and I have had to trust my intuition. This means that I may be dead wrong on certain topics, but I also may be dead on.

We were eating at a restaurant one afternoon, and Hans told me a story. He was on a mission with his unit. His unit’s job was to provide escort security for the sergeant major whenever he traveled. Hans drove Caimans in Iraq; they are armored vehicles that look like Humvees on steroids. He talked about getting out of the Caiman to take a dump. His unit started to receive incoming fire, but Hans took the time to wipe himself before going back into the vehicle. Hans told us that he could tell by the sound of the incoming rounds how far away they were. He went to describe the various sounds that bullets make depending on the distance they are from a person. It was a funny story and we laughed about it.

Later I thought about what Hans had said about the sound of the incoming rounds. How does a person learn to judge the distance of incoming fire based just on the sound of the bullets? That isn’t something that you can look up on Google. That sort of knowledge must come from personal experience. That sort of knowledge probably comes from repeated exposure to people with guns actively trying to to kill you. That tells me that Hans was shot at much more often than he initially led us to believe.

Hans also told me about life at FOB Kalsu, where he was stationed in Iraq. While he was there, his unit received mortar and rocket attacks several times a week. Hans got used to it, and they all slept in bunkers, but I cannot help to think that frequent attacks would make a person uneasy. I know that if somebody lobbed a grenade in my backyard, I would not sleep well afterward. The truth is that Hans sleeps very poorly. Part of that may be hereditary; I don’t sleep worth a damn either. However, Hans’ experience in Iraq cannot have helped matters.

Hans had almost no contact with the local Iraqis while he was there. The U.S. soldiers were actively discouraged from interacting with the people in their area. To a large extent this is understandable. Iraq was a country known for IED’s and suicide bombers. U.S. soldiers were completely unable to tell friend from foe, so everybody was treated as a potential enemy. Hans viewed all Iraqis with distrust during his six months in the country. Based on his experiences, he had some reason to fear members of the local population. So, was Hans there as an ally of the Iraqi people, or was he there as a member of an occupying force? I don’t know. I do know that Hans has no desire to ever go back to the Middle East, and that he is wary of anybody that even looks like they are Iraqi.

Hans told me about his escort missions. He talked about being on duty for twenty hours straight. He talked about going days with minimal sleep. How does a person function in that kind of environment? The answer is to that is drugs: caffeine and nicotine, in large doses. While in Iraq Hans lived on energy drinks and cigarettes. He still does. While he was at home, he started each day with a can of Monster and a Newport. That was every day, without fail. Also, while he was home, he would go out drinking with his buddies.

Nicotine, caffeine, and alcohol are integral parts of the military culture. It was like that a generation ago when I was in the Army, and it hasn’t changed one bit in the last thirty years. Hans did not have access to alcohol in Iraq and Kuwait, but he consumed plenty of nicotine and caffeine while he was deployed. The people at my office sent him and his buddies packages full of cigars, cigarettes, and chewing tobacco. They used up everything we sent them.

The Army offers a lifestyle of extremes; a soldier moves between moments of sheer terror to periods of utter boredom and back again. Legal drugs are the simplest ways of dealing with emotional problems. The three drugs I mentioned provide short term solutions, and they create long term problems. In some ways Hans is a typical soldier, dealing with his issues in the usual way. I can’t blame him. With the exception of nicotine, I used the all the same chemical fixes.

Hans told me, “Therapy is for the weak.” He was smiling when he said that, so I’m not sure if he was completely serious. Hans takes a certain perverse pleasure in messing with my head. Hans has seen an Army shrink since his return from deployment. He has some issues, and he is geting help. I am almost certain that Hans has no intention of opening up to a therapist. I think he wants chemical solutions to psychological and spiritual problems. This isn’t surprising; it’s the American way. I just know from experience that approach doesn’t work well at all. To his credit, Hans has talked about his problems to some extent. In a way, it really doesn’t matter who he tells, as long as he doesn’t keep everything inside.

Hans told me that he is skydiving. That doesn’t surprise me. He also told me that he plans on going to Air Assault School to learn how to rappel out of helicopters. That doesn’t surprise me either. Hans joined the Army for the adrenalin rush, just like I did. Whether they admit it or not, that is why most people go into the military. I got my thrills flying a Blackhawk over the trees at 100 knots, and Hans got his kicks driving a tank across the desert at 60 mph. These activities may seem pointless and immature, but they make for great stories later in life. At some point in life, all you have left is your stories.

Hans is a brave young a man. I’ve told him that. Even aside from the thrill seeking, he has shown me that he has a lot of courage. Hans has an inner strength that was probably always there, but it is more apparent to me now. I wish with all my heart that Hans had not gone to war, but since he did, I can see better who he really is. Maybe he can see that too.

Lessons Learned from Hans Part 1

Hans came home from the war. He spent three weeks with us. During that time, I tried to get to know our son again. Hans has changed since we last saw him. There are some good changes, but there are quite a few that seem unsettling. I’ve made some observations, and they are by no means objective. These are just my impressions of our son the soldier.

I have to tell you upfront that I do not and cannot understand all of Hans’ experiences. It is difficult in the best of circumstances to know the feelings and thoughts of another person. In this situation it is especially challenging because Hans has seen and done things that I have not. There is a qualitative difference between his military life and my own. Although I performed hazardous duties as an Army helicopter pilot, I served during peacetime. Hans came under enemy fire; I never experienced that. Hans killed a man; I never did. No matter what Hans tells me, I will never fully comprehend what happened to him in Iraq. There are parts of his life that I simply cannot touch.

I spent as much time with Hans as I could while he was visiting us. When he talked, I listened. Sometimes I would sit with him on our front porch, as he smoked Newport menthols and sipped on a can of Monster. Sometimes we would go out to eat and have a couple drinks. Often Hans was passive, and I had to rouse him from his lethargy to do things. I convinced him to Half-Price Books, and we stood around reading graphic novels. One time we went to Gander Mountain so Hans could look at guns.

Hans likes guns. More importantly, he understands them. While we browsed through Gander Mountain, Hans explained a number of things to me. Hans doesn’t like pistols with carbon composite stocks. He told me that the stocks are too light. He explained that, as a person fires off rounds, the balance of the weapon changes slightly and the shooter has to adjust his aim. Hans scored Expert with a pistol in basic training, and he is very familiar with the 9mm Beretta, one of the weapons he carried in Iraq. He likes the .45 revolver, but he doesn’t like the feel of a Glock. As I listened to Hans talk, it became obvious to me that he knew about weapons in a very intimate way. He talked about them in a very professionally. Rightly so. Hans is a professional soldier, and he knows his tools.

Hans always carried at least three weapons when he was in Iraq: he had the 9mm Beretta, the M-4 rifle, and a shotgun. He carried a shotgun because it was the only weapon for which he had a non-lethal round. If trouble started, he could fire the non-lethal round with the shotgun. If that didn’t have the desired effect, well, then things started to get lethal. Hans told me all about his firearms; how they worked, when they malfunctioned, how he had to clean them. For six months these weapons were his constant companions.

Hans has a conceal/carry permit from Texas, where he is stationed. He wants to buy a Beretta 9mm to conceal and carry. I asked him why he wanted to get a pistol so badly. Hans told me, “I feel naked when I am not carrying a piece.” Somehow I can understand that. Hans isn’t one of the local NRA fanatics who has a gun fetish. Instead, Hans is a man who carried a loaded weapon with him almost constantly for six of the most intense months of his life. The weapon became part of him, part of who he was. It doesn’t surprise me at all that Hans feels awkward without a firearm.

I told Hans about the shooting at the Sikh temple shortly after it happened. He listened to me, and his only question was whether or not the shooter was former military. The next day I read on the Internet that the killer was an Army vet. I told this to Hans while he was working on his motorcycle. He glanced up at me, shook his head, and said,”That really isn’t a big surprise.”

We started talking about the shooting at the temple. Hans didn’t seem particularly shocked. He remarked that people get shot each and every day, and nobody seems to care. The media doesn’t swarm around when some drug dealer gets killed, or when a kid catches a stray bullet during a drive by. Somehow people regarded this attack as extraordinary, when in reality it wasn’t. Hans had seen enough of death to know that.

Hans then told me about his feelings toward the Iraqis. Actually, he explained to me that he feels nervous and paranoid whenever he stops at a gas station or convenience store that is run by somebody who looks like they are from the Middle East. I asked him why that was; the guy in the 7–11 isn’t from Al-Qaeda. Hans told me that when “you get shot at by a person from that race”, you don’t trust people who look like that. In his head, Hans knows that the guy at the gas station is just a guy. In his gut, he doesn’t know that. Part of Hans is still in Iraq. Part of him never came home. I asked Hans how a person works through these feelings of distrust. He just shook his head at me and walked away.

Politics don’t matter. Certainly, they don’t matter to Hans. He doesn’t even vote. He told me that, while he was in Iraq, the only thing that mattered was doing his job and getting himself and his comrades back home safely. He wasn’t concerned about democracy or oil or anything like that. What mattered was caring for the welfare of his buddies and doing his duty. He doesn’t see himself as a hero or a patriot. He just sees himself as a survivor.

At age twenty-five, Hans doesn’t have much of that youthful idealism left. On the other hand, the narcissism of adolescence has been completely burned away too. Hans sees the suffering of others, and he is concerned with helping them. He knows from experience what it means to depend on other people, and what it means to have them depend on you. He now has a level of empathy that he never had before.

Hans wrestles with doubts. He told Karin and myself that he doesn’t believe in God. I’m not so sure about that. I think it is more like he doesn’t believe in God’s followers. I saw a bumper sticker once that said: “Lord Jesus, protect me from your disciples.” There is a huge disconnect between what Hans has been taught about God, and what he has experienced in God’s creation. It is obvious to Hans that people have preached one thing and then practiced something very different. Hans has been very adamant that he wants no part of the institutional church.

Before Hans ended his visit, Karin and I took him to eat Mexican food at El Senorial. It was a Saturday afternoon, and we met my younger brother, John, at the restaurant. John is Hans’ godfather. After eating and drinking, John asked if Hans would go to church with him. Hans respectfully declined the offer. After a few more beers, Hans became more amenable to the idea. In the end, all four of us went to the evening Mass at SS. Cyril and Methodius Church. Hans partcipated in the liturgy, and he received communion. I never got the impression that he was just going through the motions. He wanted it to be real.

Hans is a redneck by choice. The years in the Army and the years of living down in Texas have left their mark. One of the first things he did when he arrived at our house was to install his CB radio in his truck, along with the eight-foot whip antennas that go with it. Hans has a big, black pick up truck with two bumper stickers. One says “Army”, and the other says “Kiss my Rebel Ass”. Hans only listens to country music in his truck.

Hans likes barbecued ribs. I asked a guy at my work where to get ribs, and he suggest that we go to Speed Queen. The place is in a neighborhood that is very poor and very black. The ribs they make are execllent, and worth the trip. I asked Hans if he wanted to drive to the place on 12th and Walnut in his big, ol’ truck. Hans told me that he considered that to be a bad idea. I laughed.

I have other thoughts about Hans and the Army and the wars. I’ll get to those in the next letter.

Losing His Religion

Hans came home on Saturday. Our son was deployed with his Army unit in Iraq and then in Kuwait, and we hadn’t seen him for over a year. Hans drove up here from Fort Hood, Texas in his huge, Dodge pick up truck. He came the whole way with only making a few stops to buy gas and energy drinks. Karin and I talked with him briefly when he arrived, and then he crashed in his bedroom to sleep for twelve hours.

On Sunday morning, Karin and I got ready to go to church. I was serving as lector that day, and Karin was going to help distribute communion. Hans was up already. He had been outside smoking his first Newport of the day, and he saw that we were getting ready to leave the house. We had not asked him to come to Mass with us; we didn’t expect that he would. Hans is a reluctant church-goer; this has certainly been true since he moved away from home.

Hans is not much of a talker. He uses his words sparingly, and it is rare that he will just start a conversation on his own. However, when Hans saw that we were getting ready to go, he began talking to us. He said, “I don’t think that there is any hell except the hell on earth. There is no God. If there was a God, He wouldn’t have let me see all of that fucked up shit in Iraq.” Then he said rather definitively,”I’m not going to Mass.”

Obviously, Hans’ remarks bother me. However, I won’t attempt to refute them. First of all, any dispute at this time would be counterproductive. Secondly, I am hard pressed to show him where he is wrong. Based on Hans’ recent experiences, he has a pretty solid argument for his views. Hans killed a man in Iraq during combat. He’s seen corpses, and he’s seen intense suffering. He and his comrades have been the targets of mortars, rockets, and small arms fire. Hans has told us only a little bit about his service in Iraq, and what he has told us is grim. Hans has confronted the problem of theodicy in a very real and personal way.

How does a good Catholic boy become an atheist? I think part of the answer lies in how we taught him about God. We tend to teach our children that God is all-loving, and that somehow He will make everything all right. We focus on the image of a gentle, nurturing God who brings sunshine and rainbows. We forget about the other side of God; the God that ordered the Flood, the God who nuked Sodom, the God in the Book of Job. We have taught Hans about a God that doesn’t correspond to the events in the real world. Is it any wonder that he does not believe in Him?

One of the standard answers to problem of suffering in the world is that it is all our own damn fault. People say that all evil is due to human wickedness. That answer simply doesn’t cut it. I do not buy the notion that the sins of men cause tsunamis or typhoons. The fact is that innocents suffer, and there is no denying that. Clearly, many of humanity’s wounds are self-inflicted. Hans is a witness to that. I can understand our son’s inability to worship a deity who seems oblivious to fratricide among His children. It doesn’t make sense.

Faith is often destroyed by hypocrisy. Can I blame Hans for his disbelief when our leaders, who wear their Christian faith on their sleeves, sent Hans to fight people who had never done him any harm? Why should Hans listen to religious people who babble on about love and peace, but have no problem with our country waging endless wars?

It has been said that nobody who fights in a war returns unwounded. I know this to be true. Hans has been damaged. Physically, he looks all right. Deep inside he is just as badly injured as a person who comes home missing an arm or a leg. His soul is disfigured. He’s different. He’s changed.

Hans is correct in that there is a hell on earth. I am not sure if there is a place of eternal damnation, but I am convinced that we taste hell while we live in this world. We also experience a bit of heaven while we are here, but Hans can’t see that now. Some day he may.

Is our son lost? Maybe, for now he is. That’s okay. When he finds his way back, he will have a mature faith. Hans might not believe in God, but I still believe in Hans. More importantly, God believes in Hans.

Seeing Through Different Eyes

Back in January I went to the Islamic Resource Center in Milwaukee to sign up for an Arabic class. The Islamic Resource Center ( IRC ) is located in a building that it shares with a medical clinic near the intersection of Edgerton Avenue and 27th Street in Greenfield. The place was nearly empty the first time that I visited there. That was a pity because the inside of the IRC is much more inviting than the outside of the building. It reminds me a bit of the homes people have in Mediterranean countries; the exterior of the center seems cold and impersonal, but the interior is full of beauty and warmth. The IRC contains art and books and the faint smell of coffee. It is a place that is simultaneously exotic and welcoming.

I signed up for the Arabic class with Lee, a friend of mine from work. Lee was fascinated by the beauty of the Arabic script, and he wanted to learn how to write it. I had studied Arabic thirty-some years ago when I was in the Army, and I wanted to return to it. For Lee the class was going to be something new. For me it was going to be a process of remembering things that I had long forgotten.

Studying the language reminds me of what a woman told me when our children were in the Waldorf school. At that time the Waldorf school students learned both German and Spanish as part of the curriculum. Barb, an instructor at the school, explained to me that our children were not learning Spanish and German to necessarily become proficient in those languages. The purpose of learning Spanish was so that the child could experience a Latin soul, and the study of German was there so that the student could experience a Teutonic soul. I found Barb’s words to be very moving and very profound. A language expresses the soul of a culture. Arabic is the voice of Islam, and it is a way to experience the Muslim soul.

Arabic is at once both beautiful and harsh. The writing is an art form that seems to flow of its own accord. The spoken language is guttural, but somehow also melodious. Arabic is grounded in this world, but it can also be used to describe the works of God.

Our Arabic instructor was Abdel-latif Oulhaj, a teacher at UWM. He was good, really good. Abdel-latif was clearly a very competent teacher with a strong grasp of the subject matter. More importantly, Abdel-latif had a passion for his work. It was obvious to me that he loved the language and he loved to share it with others. Enthusiasm is infectious, and Abdel-latif was definitely enthusiastic in the classroom.

The hallmark of a good class is when a student regrets that it is over. The months went by quickly while we studied Arabic. Both Lee and I were sorry when the course was finished, because we weren’t finished. We felt like we were just getting started. The class was a beginning, not an end.

I am grateful to the people at the Islamic Resource Center for offering the Arabic class, and for providing me with the opportunity to learn more about Islam and about Arab culture. I became aware of new things. I remembered some old things. The class enabled me to see the world through different eyes.

Memorial Day

On Pentecost I served as lector during the 10:30 Mass. Immediately after the liturgy was complete, a man approached me and said, “I’m going to tell the priest this too, but you didn’t say one word about the troops! It’s Memorial Day weekend! I’m so upset about this!” The parishioner rushed off before I could respond to his remarks. He was busy tracking down our priest. His passionate comments were not completely accurate; during the prayers of the faithful, we did ask God to remember those people that had given their lives in the service of our country. Apparently, that was not sufficient for this gentleman.

If I had had the opportunity, I would have told the irate parishioner that I had served in the Army, and that our son has seen combat in the Iraq war. Fortunately, our son has survived his battlefield experience. I agree wholeheartedly that we, as Catholics, should honor our soldiers and pray for them. We should do that on Memorial Day and every day.

If I could, I would ask our congregation to pray for our troops, and then take our prayer a bit further. We ought to also pray for the civilian non-combatants in our wars, the women and children who are killed or wounded simply because they get in the way of the fighting. If we can do that, then we might also find it in our hearts to pray for the enemies of our nation. Perhaps we could pray for the members of the Taliban who have died in battle, leaving behind widows and orphans. These people are also created in God’s image, just like our son. God loves them too.

Chapter 29 A Piece of Ribbon

Napoleon Bonaparte said that a soldier will fight long and hard for a piece of colored ribbon. It’s true. Ribbons, medals, and plaques are usually without any monetary value, but a soldier will often keep them for all of his life. It’s hard to explain why this is. It might be because a particular award represents some act of courage or some level of skill. It may be that the object reminds the military person of some important event. Usually, a medal or ribbon means nothing to a person from the civilian world. It only has value for somebody that is part of the military culture. It is something that sets the soldier apart from the other people.

When Hans came home to visit us after his basic training, he brought along some of his Army certificates and awards. He had an award for marksmanship with a pistol. He had scored second best out of all the men in his unit. He was very proud of that, and he wanted me to see it. He wasn’t bragging or anything like that; he just wanted me to know what he had accomplished. It reminded me of when I had received my West Point class ring, or when I had earned my flight wings. Hans had a fancy piece of paper, and he had a piece of metal to pin on to his uniform. For him it was a big deal.

While Hans stayed with us, we took a trip one day to see my folks. Hans brought his awards with him to show to his grandfather. As we sat in my dad’s living room, Hans pulled out his treasures and let my father hold them. My dad looked at them and congratulated Hans on the fine job he had done. Hans thanked him, and then Hans seemed to straighten up just a bit.

Right above the sofa in the parents’ living room is a saber and scabbard. It was a gift from me to my folks from many years ago. I was at West Point when I bought it for them. There is a tarnished brass plaque under the saber that says: “To my parents with love”. My dad has had that hanging on the wall for over thirty years. I am almost certain that Hans has noticed it there.

During that same visit, my father gave me a little box. It contained a silver coin commemorating the service of those people that were in the military during the Korean War era. My dad said, “Here Frankie, I’m starting to give my stuff away. I figured you’d appreciate this.” I took the coin and thanked him. My dad seemed sad.

After Army basic training, Hans insisted on wearing a t-shirt that the guys in his unit had designed. The shirt had a black background with the names of the unit members written on the back of it. On the front of the shirt was a picture of a tank, along with bloody battle axes and scantily clad, anatomically improbable women. The shirt was tacky, violent, and sexist. It was also Hans’ favorite, because it reminded him of the bond that he had with the other troops that shared his struggles in basic training.

For years after I had resigned my commission, I kept my old uniforms at home. I had my dress uniform from West Point, with all of the gold braid on the sleeves and the shiny brass buttons. I kept my dress greens with the few ribbons that were attached to them. I didn’t have any medals because I had served during peace time, but I did have a pair of wings. I kept the uniforms partly so that I could show them to Hans some day. I had the uniforms in our bedroom closet until Karin decided that they would be just as happy in a suitcase in the basement. We had some flooding in the basement one spring, and for a long time none of us thought of the suitcase that had been sitting on the floor.

I eventually thought of it. The day came when I wanted to show my uniforms to Hans, and I realized that they weren’t in the closet any more. Karin told me about the suitcase and I went into the basement to find it. When I opened it I found a mass of moldy, rotted fabric. Everything the suitcase was wet and smelled bad. I threw it all out.

I was livid. Karin couldn’t understand why I was so angry. She said that it wasn’t like I was ever going to wear the uniforms again. That was true, and it was also irrelevant. I wasn’t just tossing out some old clothes; I was throwing away part of my past. Karin and I proceeded to have a loud and nasty fight. Hans commented to me years later, “Yeah, I remember that one. That’s when you and Mom started going to therapy.” Actually, that wasn’t what sent to us to therapy, but that incident did come up in conversation.

Maybe it would be better to just let go of all the accumulated military paraphernalia. It would nice to say that these trinkets no longer matter, that they no longer having any meaning or power. The problem is that they are symbols of a continuing struggle, and that story is not finished yet. These things will always exist, even if only as memories.

Iran and United States of America

Letter to Editor in Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, February 26, 2012

Dear Sirs,

Every day I read something about the deteriorating relationship between the United States and Iran. Each day there seems to be a new threat of military action by Iranians or by us. The U.S. and Iran have been adversaries since the fall of the Shah, but it seems like we have never been closer to war than we are now. I take a personal interest in this situation because our eldest son is presently deployed in Kuwait with his Army unit. If The U.S. and Iran do go to war, our son will necessarily be a part of that.

I can understand the concern of many people, especially the Israelis, regarding Iran’s nuclear ambitions. What I don’t understand is how a bombing attack on Iran by Israel and/or the U.S. will effectively end Iran’s potential for becoming a nuclear power. I cannot see how a bombing raid can make a lasting difference in Iran’s attempts to produce an atomic weapon. Bombing the Iranian facilities might set back the program for a few years, but it wouldn’t eliminate the problem.

Perhaps the idea is that if we bomb Iran, the Iranian people will rise up against their government. I don’t see much evidence in history to support that notion. It is more likely that an air attack on Iran would cause the population to rally around the mullahs. When we bombed Germany during World War II, did the Germans rise up against Hitler? When we bombed North Vietnam, was there any attempt to overthrow Ho Chi Minh?

If the dream is to achieve regime change in order to halt the nuclear research, that means we have to invade Iran. I cannot see how that would end successfully. We just finished an attempt at nation-building in Iraq, and that did not turn out well. Our efforts in Afghanistan have not achieved our goals. An invasion of Iran is bad idea, a very bad idea.

To my mind, the only rational solution is to this issue is to work out some kind of political arrangement with Iran. Unfortunately, the time available to cut a deal with Iran is limited. We are running out of time to find a peaceful solution, and avoid an unnecessary war. My son may be running out of time too.

Thinking and Feeling

Frank writes about his feelings on “reflexive killing.”

I read the article by Lt. Col. Dave Grossman about reflexive killing. The most shocking thing about reading his essay was that I wasn’t shocked. My overall reaction was, “Well, yeah, of course… “The truth is that from a military point of view everything that Grossman wrote made perfect sense. War is about killing. In particular, it is about killing your enemy in the most effective way possible. As George Patton said, “No bastard ever won a war by dying for his country. He won it by making the other poor, dumb bastard die for his country. “That statement was true seventy years ago, and its true now.

As I have mentioned before, our son was involved in combat in Iraq. His unit was ambushed. He returned fire, and he killed a man. Could Hans’ response be considered reflexive killing? I bet it was, and maybe it saved his life. A firefight is not a good time for a person to consider the moral consequences of his or her actions. There is no opportunity in a life-or-death situation to think things out. You just do it.

If the people in ROTC are teaching reflexive killing, they are just doing their jobs. A military organization is duty bound to teach its members how best to survive in combat. Unfortunately, preserving the lives of our soldiers often means taking the lives of other people. It hurts me that Hans killed someone, but it would also be terribly wrong if the Army had not adequately trained our son to defend himself when attacked. I wasn’t there, but it sounds like Hans reacted as he was trained to do. He probably did not have the time to think or to feel.

Well, now he does. Hans will have the rest of his life to replay the movie in his head. He didn’t want to tell us about the attack, but then again, he felt like he needed to say something about it. I believe that it bothers him at some level, and I don’t think that feeling will go away for quite a while. Hans will make peace with his actions, but he has been changed by them. Reflexive killing is a short term solution that results in long term problems. Hans survived the attack. Now he has to survive the aftermath.

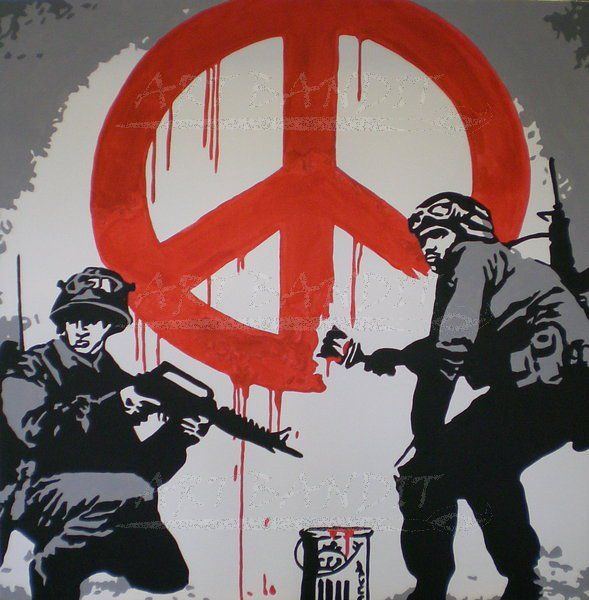

Rather than focusing on the instruction of young people in reflexive killing, it might be more useful to look at the reasons why they find themselves in a position that necessitates the use of violence. It is too late to stop the action when a young man is driving through the Iraqi desert and gets attacked by people who really hate him. That is way too late to change anything. We have to stop the violence well before the crisis occurs.

I suggest we ask questions. Why do young people like Hans enlist or join ROTC? Why did I go to West Point? Why do we, as a nation, keep sending our youth to fight people that they don’t know or understand? What opportunities can we offer to young persons that allow them to demonstrate their courage and commitment without taking other human lives? We need to look at the circumstances that set the stage for war. We have to get ahead of the game. Once somebody signs on the dotted line and makes a commitment to the military, it is too late to tell them killing is wrong. We have to influence people before they make the choice to be soldiers. We can’t wait until they pull the trigger.

Maybe I Heard Him Wrong

Frank publishes this essay with the permission of his son Hans who is now serving in the military in Kuwait.

Hans flies back to his unit in Kuwait today. He has been on his mid-deployment leave for the last two weeks. He spent his time in Texas with his friends, some of our family members, and his big, ol’ Dodge pick-up truck. Karin and I had hoped that Hans would come up to Wisconsin to visit us, but that didn’t happen. He has called us a number of times while he’s been in the U.S., and we talked quite a bit.

I came home from work around noon on Wednesday, and Karin told me that Hans had called her in the morning. They had talked for awhile about small stuff, and then Hans had talked a little about his time in Iraq. Karin told me that Hans had said that, while in Iraq, he had shot a dog. Apparently, the dog was wild and aggressive. Then Karin told me that Hans had said something odd: he had told her that he had shot somebody, but it hadn’t bothered him that much. Karin said that maybe she hadn’t heard him correctly, and that Hans had been still talking about shooting the dog. Maybe she had misunderstood him.

I shrugged it off. I hadn’t been there for their phone conversation, so I had no idea what Hans had actually meant to say. I was tired, and I took a nap for a while.

Wednesday evening, I was home alone in the house. The phone rang. It was Hans. We talked. He told me about his truck and all the detailing that he was having done on it. We talked about the weather down in Texas. Hans told me that he was getting antsy about going back to his unit. He mentioned that he kind of missed how everybody in his company had worked together while they were in Iraq. He told me how all the guys had really looked out for each other while they were there.

I said to Hans, “Mom told me that you had to shoot a dog in Iraq. Did you? “

Hans said, “Yeah, it attacked me and it was biting my hand, so I had to kill it.”

I paused for a moment, and then I asked him, “When you were in Iraq, did you shoot someone?”

Hans immediately replied, “Yes.” No hesitation. I had asked a simple question, and he had given me a straight answer.

I took a breath. Then I asked him, “Did he die?”

Hans said, “Well, yeah, I guess so…I must have pumped thirty rounds into him.”

“Aaaaw fuck “, I thought.

Hans said, “ There was an ambush…they bombed the first vehicle…we fired back.”

I said, “ I’m sorry, Hans. I’m sorry that had to happen. I’m sorry that you were in that situation.”

Hans replied, “It didn’t really bother me. I slept okay that night. I’m all right.”

Hans was very quick to tell me that he was okay. I wonder if he said that because it is true, or because he wanted to reassure me, or because he is trying to convince himself that he is all right. Maybe it is a combination of all three things.

Hans told me, “Hey, don’t tell Mom. I don’t want her to freak out. “

Well, I told Mom. How could I not? She didn’t freak out, but it hurts her. I waited a couple days to talk to Karin about it, but she needed to know. She had to know.

I told Stefan too. He needs to know what happened. It may not change his decision to join the Army, but he needs to understand what is real.

I talked to some guys at work about Hans. Most of them are vets; some saw combat. One friend of mine who was in Vietnam told me, “Frank, be proud of him. He did his job!”

That’s true. I am proud of Hans. He is a very brave young man. He did what he had to do to defend himself and his comrades. But still…

A man is dead. I know nothing about the man that Hans shot. Hans probably doesn’t either. I do know that all life is sacred. I do know that every human life is precious. I do know that somebody, somewhere mourns for this man.

I am grateful that Hans is alive and unhurt. However, I believe that this will leave a mark. It will change Hans, and this event will affect any number of people, now and in the future. Karma is real, and things have been set in motion. Every death is a tragedy, but not every death is a waste. It is possible for good to come of this. It depends on how we react to the event. It depends on what we learn from it.

In a way, it seemed odd that Hans didn’t come up to visit us. Now it makes more sense. It was probably hard enough for him to say what he needed to say over the phone. It would have been much harder for him to look us straight in the eye and say it.

I am grateful that Hans told me what he did. That shows that he trusts us and loves us. He knows that we love him. I spoke with our priest, and told me to be patient and to wait. He suggested that I be there for Hans, if and when he decides to speak about this again. He told me to listen. I’ll do that. I can do that much.

Please pray for Hans. Pray for the man that died. Pray for us all.

It is still hard for me to accept what Hans told us. Maybe I heard him wrong.

Politicians Mocking Sacrifice of Soldiers

Letter to editor of Milwaukee Journal Sentinel of Dec. 21, 2011

Our son just arrived in Kuwait from Iraq a couple days ago. He was one of the last troops to leave Iraq. His recent deployment in Iraq has been very stressful for my wife and myself. People have tried to reassure us by telling us that he is defending our nation’s freedom. They say that our son is risking his life to protect the rights that we hold dear.

It is more than a little disturbing that, while our son is serving overseas, the Congress of the United States has been actively working to undermine the Bill of Rights. Both houses of Congress overwhelming passed the National Defense Authorization Act of 2012 which, in Section 1031, allows the military to arrest and indefinitely detain any suspected terrorist without that person being able to have access to a lawyer or a trial. This would apply to any U.S citizen at any time, anywhere on U.S soil. People might try to dismiss this and say that the law will only affect terrorists, but this law is a direct assault on the rights of every American. If President Obama signs this law, nobody is free.

It is hard enough for us to worry about our son as he serves his country overseas, but we know that he is doing what he believes is right. He is defending the U.S. Constitution. His comrades are doing the same. It is an absolute travesty to watch our elected officials make a mockery of the sacrifices of these soldiers.

The Recruiter

On Wednesday Stefan announced to us that he had invited the high school’s Army recruiter to visit our home at 3:15 PM the following day. I don’t know if Stefan’s ADD kept him from giving us any more notice, or if he just likes the element of surprise. Stefan had mentioned his desire to join the Army previously, but Karin and I had hoped that this was only a passing fancy. I guess not.

Stefan got home from school just before the recruiter showed up on Thursday. Stefan seemed excited about the visit. Generally, he embodies that adolescent sort of ennui, but not on Thursday. He kept looking out the window for the soldier to pull up in his car, and he quickly went outside to greet him when he did show up.

I had made some coffee before hand. We all sat around the kitchen table; Karin, Stefan, the recruiter, and myself. The sergeant introduced himself and then started his spiel: “Well, I’m kind of a visual guy, so I brought some papers here for us all to look at…”

I responded, “ Naaah, I don’t want to look at those.”

The soldier looked at me and said, “ Okay, well, we don’t have to look at these forms right now. Stefan approached us and told told us that he is interested in enlisting.”

I turned to Stefan and said, “ My impression is that Stefan has his heart set on joining the military. Is that right?” Stefan nodded. The sergeant turned to us and said, “And I assume that you folks approve of this?” Karin and I simultaneously replied, “NO.” Awkward pause. I said to the recruiter, “ So, is there anything else we need to talk about?” The sergeant looked at me and asked, “ Sir, were you in the military? I noticed you have a footlocker with “ 2LT “ stenciled on it.”

I had forgotten about the footlocker. It sits on the floor in the hallway, filled with stuff that I should have tossed out years ago. I had been issued the footlocker just before graduating from West Point, and had been told to stencil my name “ 2LT Francis K. Pauc “ on the top of it. That was back when most of my worldly possessions fit into the footlocker. I wonder what other relics of that part of my life are scattered throughout our house.

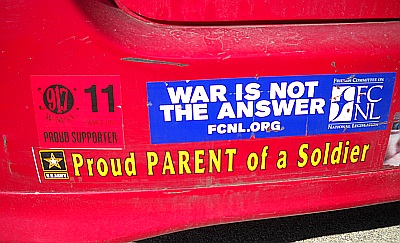

I told the recruiter that, yes, there had been a time when I was a second lieutenant. Then I asked him if he had seen the sign in our front yard that said “ War is not the Answer”.

He replied, Yes Sir, I saw your sign. Everybody has the right to his own opinion.” Glad to hear it.

Enough of the small talk. I gave the sergeant a brief history of our family. I told him that I had gone to West Point and then served six years as an officer during the Cold War era. I explained that later I had become an anti-war activist, and that then, through an ironic twist of fate, our eldest son had joined the Army, and that he is presently deployed in Iraq. I tried to make it clear that having one son overseas was hard for us, and that the prospect of having both our sons at war was a bit too much to handle.

I mentioned that Hans, our oldest boy, has called us once from Iraq to let us know that he was okay. Hans had said that he hadn’t been shot at for several weeks, and that the neighbors only tossed mortars on to the base a couple times a week. Oddly enough, Karin and I didn’t find his words comforting.

The recruiter said that we were drawing our forces out of Iraq, and it was getting better. I told him that Hans was going to be one of the last troops to leave Iraq. He will probably turn off the lights and lock the door on his way out. However, he is staying with his unit in Kuwait because the odds are that something else will go to hell in one of the other nearby vacation spots.

The sergeant said that he had been in Iraq for twenty-seven months, and that overall it had been a good experience for him. Maybe so. The recruiter also told us that his fiance had been in the service for five years, and she had never been deployed overseas. Then he mentioned that she was a dental hygienist. Apparently, oral hygiene is not a big priority in the desert.

The truth is that if Stefan enlists, he will get deployed. Guaranteed. I remember when Hans graduated from basic training, his commander said flat out that all his troops were getting deployed. It wasn’t a matter of “if”; it was just a matter of “when” they would go.

I told the sergeant that soon Stefan would be an adult, and he could make his own decisions on the matter. In a few weeks my opinion won’t matter; it might not even matter now. He will do what he needs to do. I respect that. I am willing to accept Stefan’s choice, but that doesn’t mean that I have to like it. I won’t do anything to try to stop Stefan from enlisting, but I won’t cheer him on either. The recruiter said, “ Sir, we don’t try to push parents to sign a waiver before the young person is of age.” I replied, “Good, because I’m not signing anything.” Stefan smirked.

The sergeant asked Stefan what he hoped to do in the Army. Stefan told him that he wanted to be a mechanic. The recruiter explained that Stefan had taken the aptitude test, and that his chances for becoming a mechanic were good. He said, “ It all depends on this young man’s test scores and on his choices…” I interjected, “And on the needs of the Army.” The sergeant looked at me and chuckled, “Yes, and on the needs of the Army.”

The Army, like most organizations, will promise a new recruit damn near anything, but this usually done in good faith. However, when push comes to shove, the Army will do what it wants with you. Stefan might get trained as a mechanic, but if the Army needs him to carry a rifle instead of turning a wrench; then, by God, he’s going to carry a rifle. That’s how it works.

I told the recruiter that my main concern wasn’t that Stefan might get hurt. Stefan just broke his thumb doing bike tricks. Two years ago, I had my leg crushed by a forklift at work. You don’t have to go far to get hurt. My real concern is that Stefan gets put into a situation where he has to take the life of another human being. Killing a person, justifiably or not, scars the soul of the killer. The recruiter mentioned that he was an aircraft mechanic himself, and that he had never had to fire his weapon. That’s true, but that might have just been dumb luck. I mentioned that I had never been in a war, and I was okay with that. However, right now, our country is at war, and it is kind of crap shoot as to whether or not a soldier will have to kill somebody else.

The recruiter kind of glossed over the fact that Stefan would be trained how to shoot and do all of that sort of thing. He focused on the idea that Stefan would be trained as a mechanic. I told him that as a plebe, I learned that the job of an Army officer was to be “ an expert in the management of violence “. That implies hurting somebody. Soldiers kill people. That is what armies do. Stefan needs to understand that. I made sure that Stefan heard all of this.

The discussion wound down. I told the recruiter that the date to remember is February 9th, 2012. That is Stefan’s birthday. When that day rolls around, it’s game on. Until then, we’re done talking. The sergeant took his leave, and we all said goodbye. His seemed eager to go. Stefan wanted to go too. I gave him a hug.

Stefan plays guitar, and he writes his own songs. I am kind of lame bass player. I told Stefan that, before he leaves for basic training, he and I will record a song together. He can write it. I’ll play whatever he wants. I have a friend from work who is a drummer, and he will help us out. Another friend, who is a blues guitarist. will help with the recording. I want to have one song with both of us playing. I want to have something to listen to when Stefan is far away.

Not Really that Surprised

After Mass on Sunday, Stefan announced to Karin that was enlisting in the Army as soon as he turned eighteen. Well, actually he can’t join up until after he graduates from high school in June. The Army requires a person to have a diploma. Stefan seems to have his heart set on becoming a soldier; I didn’t notice any hesitation at all when I talked to him about it. This turn of events is hard for Karin and me. Our oldest son, Hans is still deployed in Iraq. We never expected to have both of our sons in the military.

Karin was clearly upset by Stefan’s decision. She complained about the fact that military recruiters were in the schools, talking to minors. I’m not sure that eliminating recruiters from Stefan’s high school would have made that much of a difference. If a person wants something, he will find it. If Stefan really wanted to learn about the Army, he would have found the necessary information easily enough, even without any soldiers in his school. I know that the recruiters use propaganda effectively, and I doubt that they tell young people the whole story. They are there to sell a product, and they use whatever gimmicks they have available to attract teenagers. In all fairness, despite the smoke and mirrors, the recruiters do have something tangible to sell. They can offer things that actually are of value.

J.P. Morgan once said, “ A man always has two reasons for doing anything: a good reason and the real reason.” When I first talked with Stefan about his enlistment, he gave me all the good reasons for doing it. He told me about learning to become a mechanic, about getting money for school, and that sort of thing. Later, I talked with Stefan again, because I wanted to hear the real reasons.

I asked Stefan to sit down with me for a while. I asked him if he was angry with us. He said that he wasn’t. I asked him if he understood that what he was doing would hurt his mom. He told me that he knew that. I asked him if all of this had anything to do with getting the hell out the house, and becoming independent. He emphatically said, “Yes.”

There is a lot to be said for leaving home and starting a life on your own. It takes guts, and it is remarkably difficult to do in our times. Many young people are staying home with their parents strictly for economic reason. Does a guy in his mid-twenties really want to have his mom asking when he’s going to be home at night? No. Young adults are stuck at home because they can’t find a decent job that will allow them to function independently. Sadly, the military is one of the few options that will allow a young person to move out and spread his or her wings.

I asked Stefan what else was on his mind. He looked at me and said, “I want to have an adventure.” I sighed. I know how that feels. I wanted an adventure when I was his age, and I went to West Point. Adventures are good things. They carry with them an element of risk, and they force a person to grow up. A young person like Stefan wants to see the world; our house and our town are too small for him now. A person has to roam and wander before he can settle down. Stefan could easily get a job here as a welder, and make good money at it. But if he gets a steady job now and stays put, will he wonder later what it’s like in the big, wide world? I suspect that he would wonder, and I suspect that he would regret putting down roots before he had experienced other places and people.

Stefan is physically very active. He just broke his thumb while riding his trick bike on the half pipe. He likes to push himself and stay fit. He wants to try things that are difficult to do. He wants to test himself. I can see how the Army would attract him.

While we talked, I remembered things. I remembered some of what I did when I was in the Army. I remembered qualifying as a marksman with the M-16. I was about Stefan’s age, standing in foxhole, and leaning on a wet sandbag, trying to pick out dark green targets that popped up from the morning fog that swirled in the distance. I remembered firing off a round, and sniffing the acrid smell of gunpowder. I can still hear the loud “pop “ as I pulled the trigger, and then the tinkling sound as the hot, brass cartridge fell to the ground next to me.

There were other memories too. I remembered walking across a glacier in Alaska. I remembered the first time that I flew solo in a helicopter. I remembered being in the Mojave Desert and seeing the moon rise over the mountains. Some of the memories sucked. There is a lot about the Army that is brutal and vicious and stupid. However, despite all of that, a lot of it was fun.

I asked Stefan if he understood that he might be put into a position where he would have to kill another human being. He said that he understood. Maybe he really doesn’t understand what that all entails, but I do believe that he has thought about it in a serious manner. That is all that anybody can do.

I did not and I will not tell Stefan what to do. He knows how we feel about this decision. He is an intelligent young man with a big heart and a stubborn streak. He has to follow his own conscience. In reality, he is doing pretty much the same thing I did thirty-five years ago for almost exactly the same reasons. I can’t fault him. I am sad that I don’t have a good counter-offer. I really don’t. I wish I did.

Essay for the Zen Center newsletter

Father at War bumper stickers Us and Them

When I joined the Army, many years ago, I was issued an olive drab, scratchy, woolen blanket that had the letters “ US “ stenciled on to it. I asked another soldier why the Army insisted on writing “ US “ on all the blankets. He told me that it was so we knew that the blanket was ours. Then he smiled and told me that the word “ THEM “ was written on all of the Soviet blankets.

Us and them. The eternal desire of humans to choose sides. Where does it all start? Do you remember the first time that you picked players for your kickball team? The idea of people being “ either/or “ is deeply ingrained in our minds and hearts. We spend our lives separating the sheep from the goats, and other people do the same for us. We want to know who is with us and who is against us. Why?

Choosing sides is a way of defining ourselves, albeit in a negative manner. Instead of looking at who we are, we look at who we are not. We can say things like, “ I am not a fundamentalist, “ or “ I am not a Democrat “, and we effectively build a fence around our lives. We decide to whom we will listen, and who we will ignore. We attempt to establish an identity through aversion. It’s a hollow sort of identity, because even if we cut off all the people we dislike, we still don’t know who we are. We’ve only made our world a lot smaller.

Defining ourselves is a waste of time anyway. Zen makes it clear that we don’t really know who we are. Other traditions say the same thing. Christians from St. Paul through Thomas Merton have said that we see through a glass darkly, that we do not and cannot really understand ourselves. I often have to use the loudspeaker at work to call somebody to the office. There is a time delay on the intercom, and I hear my words a few seconds after I say them. I always think about how strange my voice sounds, and I wonder if that is really how I sound to the rest of the world. If I have trouble recognizing my own voice, how can I recognize the person inside my head?

As Pink Floyd sang in “ Us and Them “ :

“And who knows which is which and who is who,

Up and Down,

And in the end it’s only round and round and round…”

Who we are is a mystery that we cannot solve, and we exhaust ourselves in the attempt.

Perhaps each person has a unique, immortal soul that is their true self. Even if this is true, a person can never fully experience that self. I know that I can’t. What I experience is the shifting, changing personality that responds when somebody yells the name “ Frank “. It is hard for me to see that I am constantly changing, and hopefully growing. Other people point it out to me, and sometimes they don’t do that in pleasant ways. Most of my classmates from West Point do not acknowledge me any more because the man they knew, or thought they knew, thirty years ago is gone. I still have the same DNA and social security number, but I am no longer the person I was at age twenty-three.

“Don’t know “ mind helps. Once I accept the fact that I do not know who I am or what I am, then I can become whatever I need to be. It’s an oddly liberating notion. If I can’t figure out who I am, then it is a useless to try to define others. “ Don’t know “ leads to the idea that all things are in a state of flux, and all things are connected. If all things are connected, then there is no “ us and them “. There is only us.

What do We have to Offer?

Two weeks ago my wife answered our home phone. To her dismay, the person calling was a Marine recruiter looking for our youngest son, Stefan. Stefan is a high school senior, seventeen years of age, and very athletic. To a recruiter our son is fresh meat. My wife, Karin, was a bit freaked out by this call because our oldest son, Hans, is presently deployed in Iraq with his Army unit. Our immediate thought was, “ Oh no, not another soldier in our family. “ We asked Stefan about this recruiter, and he denied having ever spoken with the man. That’s a good answer. We were okay with that.

I was reminded of this incident on Saturday when Karin and I were at the Milwaukee City Hall for the rally against the war in Afghanistan. One man spoke to the group about the need to get proponents of nonviolence into the schools to talk to the students, just like the military recruiters do. I thought about that, and I asked myself the question, “ What would we say to these kids? “ How would we counteract the propaganda of the military recruiters?

I’m afraid that anybody trying to argue against the message of the U.S. military in our schools is at a great disadvantage. We can say that the recruiters rely on flashy advertising, and that they tell the young people only half the truth. However, even if they quite often use smoke and mirrors to confuse the unwary, it has to admitted that they actually have something real and physical to sell. They can offer money and benefits and jobs. Therein lies the problem for people trying to oppose the war machine. We don’t often offer much that is tangible.

As a case in point, I would have to say that, for the first time in his adult life, Hans has some measure of financial security. In the Army he has a steady paycheck, he has health benefits, and he has a roof over his head. Granted that isn’t much, but it is more than he had before when he was struggling to find work. In theory, he could retire from the Army with a pension in his forties. What do we, as peacemakers, have as a counter offer? Nothing. There aren’t many career fields in nonviolence. In economic terms, we don’t have anything to give a young person trying to make it in the world. This is a problem.

I don’t know why young women join the military. I do know why young men join up. So, I will restrict the next set of comments to my area of expertise, and look at what the military has that young men would want.

Young men want an adventure; not all of them, but many of them do. In any case, guys that are attracted to the military are restless and ambitious. They want to see the world, and they want to change it. I remember that when I went to West Point, there was a song on the radio from Simon and Garfunkel called “ My Little Town “. The chorus of the song was, “ Nothing but the dead and dying in my little town! “ That was my theme. I couldn’t get away from home fast enough or far enough. I wanted to experience everything that I could as fast as I could. To a large extent the Army satisfied that desire. It still does, and it sells that. As proponents of nonviolence, do we offer young men an adventure?

A young man also wants to prove himself. When I was at West Point, I had somebody telling me the entire time I was there that I would never be good enough to graduate. Well, I did graduate, and mostly it was to prove that I could. A young man needs a rite of passage, and in a perverse sort of way, the military provides that. If we are to promote nonviolence, we have to provide that too. There has to be some kind of challenge involved.

The military has all the best toys. I know that sounds silly, but it is God’s truth. I remember flying Blackhawk helicopters, and it was a rush. Hans likes to drive tanks. Young men like to fire large caliber weapons. There is a strange ecstasy in blowing up inanimate objects. It’s fun; it just is. I’m sorry, but we can’t match the military in this area. This is what they do best.

It seems to me that we generally talk to young people about war in the same way that we talk to them about using drugs or engaging in risky sexual behavior. We rely heavily on fear tactics and on an appeal to morality. So, how well have we done with keeping kids clean and sober? How many virgins do we have out there? We may influence a few young people by taking about the horrors of war, but often in their minds they believe that they are immortal and they cannot imagine any harm befalling them. We have meet the youth where they are. We can’t rely on the arguments that appeal to old men.