This page will feature articles that have come across my desk. It will be like an internet magazine of articles that interest me (and may or may not interest you).

On this page… (hide)

- It Was Oil, All Along

- Rome: Churches appeal to world leaders to feed the hungry

- Where Industry Once Hummed, Urban Garden Finds Success

- Iraq Boy’s Family Describes Fatal Blast

- Turkish Schools Offer Pakistan a Gentler Vision of Islam

- An Open Letter to His Eminence Francis Cardinal George, OMI,

- Counting Iraqi Casualties & a Media Controversy

- A Man of Peace: Gordon C. Zahn, 1918-2007

- Testimony of a US ex-marine

- What’s your consumption factor?

- At Christmas, Iraqi Christians Ask for Forgiveness, and for Peace

- Following Conscience

- Primitive impulses of war

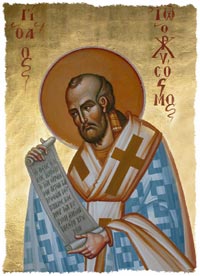

- St John Chrysostom, Almsgiving, and Persons with Disabilites

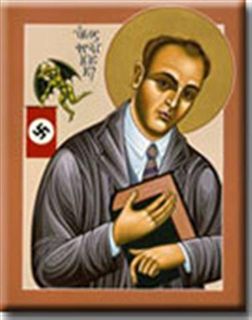

- Franz Jägerstätter: A hard history to face

- What The Constitution Says About Iraq

- The War As We Saw It

- Power In Powerlessness

- On July 4, Put Away the Flags

- The War Inside

- Jasmine’s death was collateral damage in a culture of violence

- A soldier son serves and dies. Did his father fail him?

- Remembering Our Returning Soldiers with Mental Health Illnesses

- Guns and American values — Editorial from The Tablet (London) / 21 April 2007

- About Perception and Parity

It Was Oil, All Along

http://www.pbs.org/moyers/journal/06272008/watch3.html

Saturday 28 June 2008

by: Bill Moyers and Michael Winship

Oh, no, they told us, Iraq isn’t a war about oil. That’s cynical and simplistic, they said. It’s about terror and al-Qaeda and toppling a dictator and spreading democracy and protecting ourselves from

weapons of mass destruction. But one by one, these concocted rationales went up in smoke, fire and ashes. And now the bottom line turns out to be … the bottom line. It is about oil.

Alan Greenspan said so last fall. The former chairman of the Federal Reserve, safely out of office, confessed in his memoir,”Everyone knows: the Iraq war is largely about oil.” He elaborated

in an interview with The Washington Post’s Bob Woodward, “If Saddam Hussein had been head of Iraq and there was no oil under those sands, our response to him would not have been as strong as it was in the first Gulf War.”

Remember, also, that soon after the invasion, Donald Rumsfeld’s deputy, Paul Wolfowitz, told the press that war was our only strategic choice. “We had virtually no economic options with Iraq,” he explained, “because the country floats on a sea of oil.”

Shades of Daniel Plainview, the monstrous petroleum tycoon in the movie, “There Will Be Blood.” Half-mad, he exclaims, “There’s a whole ocean of oil under our feet!” then adds, “No one

can get at it except for me!”

No wonder American troops only guarded the Ministries of Oil and the Interior in Baghdad, even as looters pillaged museums of their priceless antiquities. They were making sure no one could

get at the oil except … guess who?

Here’s a recent headline in The New York Times: “Deals With Iraq Are Set to Bring Oil Giants Back.” Read on: “Four western companies are in the final stages of negotiations this month on

contracts that will return them to Iraq, 36 years after losing their oil concession to nationalization as Saddam Hussein rose to power.”

There you have it. After a long exile, Exxon Mobil, Shell, Total and BP are back in Iraq. And on the wings of no-bid contracts - that’s right, sweetheart deals like those given Halliburton, KBR

and Blackwater. The kind of deals you get only if you have friends in high places. And these war profiteers have friends in very high places.

Let’s go back a few years to the 1990′s, when private citizen Dick Cheney was running Halliburton, the big energy supplier. That’s when he told the oil industry that, “By 2010 we will need on the

order of an additional fifty million barrels a day. So where is the oil going to come from? While many regions of the world offer great oil opportunities, the Middle East, with two-thirds of the world’s oil and the lowest cost, is still where the prize ultimately

lies.”

Fast forward to Cheney’s first heady days in the White House. The oil industry and other energy conglomerates were handed backdoor keys to the White House, and their CEO’s and lobbyists

were trooping in and out for meetings with their old pal, now Vice President Cheney. The meetings were secret, conducted under tight security, but as we reported five years ago, among the

documents that turned up from some of those meetings were maps of oil fields in Iraq - and a list of companies who wanted access to them. The conservative group Judicial Watch and the Sierra Club

filed suit to try to find out who attended the meetings and what was discussed, but the White House fought all the way to the Supreme Court to keep the press and public from learning the whole truth.

Think about it. These secret meetings took place six months before 9/11, two years before Bush and Cheney invaded Iraq. We still don’t know what they were about. What we know is that this is the oil industry that’s enjoying swollen profits these days. It would be laughable if it weren’t so painful to remember that their erstwhile cheerleader for invading Iraq - the press mogul Rupert Murdoch - once said that a successful war there would bring us $20-a-barrel oil. The last time we looked, it was more than $140 a barrel. Where are you, Rupert, when the facts need checking and the predictions are revisited?

At a Congressional hearing this week, James Hansen, the NASA climate scientist who exactly twenty years ago alerted Congress and the world to the dangers of global warming, compared the chief executives of Big Oil to the tobacco moguls who denied that nicotine is addictive or that there’s a link between smoking and cancer. Hansen, whom the administration has tried again and again to silence, said these barons of black gold should be tried for committing crimes against humanity and nature in opposing

efforts to deal with global warming.

Perhaps those sweetheart deals in Iraq should be added to his proposed indictments. They have been purchased at a very high price. Four thousand American soldiers dead, tens of thousands

permanently wounded, hundreds of thousands of dead and crippled Iraqis plus five million displaced, and a cost that will mount into trillions of dollars. The political analyst Kevin Phillips

says America has become little more than an “energy protection force,” doing anything to gain access to expensive fuel without regard to the lives of others or the earth itself. One thinks again of

Daniel Plainview in “There Will Be Blood.” His lust for oil came at the price of his son and his soul.

Bill Moyers is managing editor and Michael Winship is senior writer of the weekly public affairs program Bill Moyers Journal,which airs Friday nights on PBS. Check local airtimes or comment at The Moyers Blog at www.pbs.org/moyers . This comment was

presented on Friday 27 June 2008 on Bill Moyers Journal.

Rome: Churches appeal to world leaders to feed the hungry

“Give food to those who are dying of hunger because if you do not, you shall have killed them,” (Pope Benedict XVI)

This article speaks for itself, especially the statement by the head of World Council of Churches: “Human actions that are driven by greed have created poverty, hunger and climate change. Humanity must be challenged to overcome its greed.” (Rev. Samuel Kobia)

Ecumenical News International / 5 June 2008

By Peter Kenny

Rome, 5 June (ENI)--The world converged on Rome this week for an international summit on food and security, with some countries using it as a political platform, but the message from churches and faith communities was unequivocal: feed the hungry.

“Give food to those who are dying of hunger because if you do not, you shall have killed them,” warned Pope Benedict XVI in a message to the Food and Agriculture Organization that Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone, the Vatican’s secretary of state, read at the Rome headquarters of the UN body dealing with food and agriculture.

The 3 to 5 June FAO summit sought to tackle skyrocketing food prices, and food shortages, as well as farming problems in some cases attributed to climate change as well as the use of grains in bio-fuel production, and rising energy consumption in emerging economies.

“Ensuring food security for all of the world’s people is among the greatest challenges facing humanity in the early years of the 21st century,” the Geneva-based World Council of Churches said in a statement commenting on the Rome summit.

“The WCC views the primary cause of the current crisis as inappropriate human actions, which have induced climate change and skyrocketing food prices,” declared the WCC general secretary, the Rev. Samuel Kobia. “Human actions that are driven by greed have created poverty, hunger and climate change. Humanity must be challenged to overcome its greed.”

The WCC head said that churches have an essential role to play on this issue, and to be effective they must face the global food crisis together.

Meanwhile, and commenting further on the general issue of global food and security, WCC general secretary Kobia commented, “While churches and agencies of Christian witness have provided important services in the past, there is so much more that we could achieve. Individually and collectively, the time has come for churches to reassess and strengthen their policies of advocacy and support in addressing this crisis.”

Sushant Agrawal, director of the Church’s Auxiliary for Social Action in India, said, “If God’s will was done, no one would go hungry.” Agrawal, who is also the moderator of the Geneva-based ACT International aid group, added, “The Lord’s Prayer highlights that having enough to eat is and has always been central to the Christian idea of a world shaped by justice and mercy.”

While the summit was taking place in Rome, churches around the world shared information about their work on the underlying causes of the current desperate situation. The World Council of Churches, ACT International, ACT Development and the Ecumenical Advocacy Alliance asked those associated with them what campaigning they were taking around the food crisis, along with any humanitarian or long-term development assistance.

The Geneva-based groups said that at present 854 million people, representing one person in every eight, are hungry. The groups noted that, “The current crisis caused by rapid increase in food prices” could add another 100 million people to that count.

Separately, a coalition of more than 250 faith-based organizations attending the Rome summit called on the conference to launch an “effective, long-term multi-stakeholder process of discussion and action at national, regional and international levels, based on fundamental spiritual values in which civil society, including faith organizations, will play a full role”.

The groups circulated a statement to all delegations at the Rome summit. The signatory organizations include Roman Catholic religious orders, non-governmental organizations, a number of who have consultative status at the UN Economic and Social council, various churches, and ecumenical inter-church aid networks.

Their statement said, “Every faith tradition invites us both to feed the hungry and care for our environment and its myriad life forms … We also recognize the need to ensure that policies enacted by elected representatives and relevant international organizations contribute to an improved quality of life for every human person, each made in the image and likeness of God, and to the sustainability of ecosystems on which every living creature depends.”

Where Industry Once Hummed, Urban Garden Finds Success

By JON HURDLE

Published: May 20, 2008

New York Times

Kacie King checked honey

production at the North Philadelphia

farm, Greensgrow, which provides

fresh food where it is rare. PHILADELPHIA — Amid the tightly packed row houses of North Philadelphia, a pioneering urban farm is providing fresh local food for a community that often lacks it, and making money in the process.

Greensgrow, a one-acre plot of raised beds and greenhouses on the site of a former steel-galvanizing factory, is turning a profit by selling its own vegetables and herbs as well as a range of produce from local growers, and by running a nursery selling plants and seedlings.

The farm earned about $10,000 on revenue of $450,000 in 2007, and hopes to make a profit of 5 percent on $650,000 in revenue in this, its 10th year, so it can open another operation elsewhere in Philadelphia.

In season, it sells its own hydroponically grown vegetables, as well as peaches from New Jersey, tomatoes from Lancaster County, and breads, meats and cheeses from small local growers within a couple of hours of Philadelphia.

The farm, in the low-income Kensington section, about three miles from the skyscrapers of downtown Philadelphia, also makes its own honey — marketed as “Honey From the Hood” — from a colony of bees that produce about 80 pounds a year. And it makes biodiesel for its vehicles from the waste oil produced by the restaurants that buy its vegetables.

Among urban farms, Greensgrow distinguishes itself by being a bridge between rural producers and urban consumers, and by having revitalized a derelict industrial site, said Ian Marvy, executive director of Added Value, an urban farm in the Red Hook section of Brooklyn.

It has also become a model for others by showing that it is possible to become self-supporting in a universe where many rely on outside financial support, Mr. Marvy said.

Mary Seton Corboy, 50, a former chef with a master’s degree in political science, co-founded Greensgrow in 1998 with the idea of growing lettuce for the restaurants in downtown Philadelphia.

Looking for cheap land close to their customers, Ms. Corboy and her business partner at the time, Tom Sereduk, found the site and persuaded the local Community Development Corporation to buy it and then rent it to them for $150 a month, a sum they still pay.

They made an initial investment of $25,000 and have spent about $100,000 over the years on items that included the plastic-covered greenhouses and the soil that had to be trucked in to cover the steel-and-concrete foundation of the old factory site.

“The mission was: How do you take postindustrial land and turn it into some kind of green business?” said Ms. Corboy, an elfin woman with the ruddy cheeks of someone who works long hours out of doors.

She approached her early lettuce-growing operation with conventional business goals and little thought for what an urban farm could achieve.

“I thought you didn’t have to have a relationship with the community,” she said. “You would just be a business person.”

Customers said the farm was a breath of fresh air in a gritty neighborhood.

“It’s a little piece of heaven,” said Janet McGinnis, 47, who lives on nearby Girard Avenue. “We live in the city, and it makes me feel good to wake up and see flowers.”

Ms. McGinnis said she could buy herbs, bread and produce elsewhere but did so at Greensgrow because it is part of the community. “We’ve got to keep it in the community,” she said. “We have to give back.”

Despite the community goodwill, the farm lives with urban problems like theft and violence. “I have gone through every tool in the box eight or nine times,” Ms. Corboy said.

Although no one at Greensgrow is getting rich from the operation — after 10 years’ work, Ms. Corboy is making an annual salary of $65,000 — there is a sense that their time has come.

“Ten years ago when I said we were going green, people thought we were out of our minds,” Ms. Corboy said. “Now we are top of the party list.”

Iraq Boy’s Family Describes Fatal Blast

Parents Tell ABC News About the US Bombing that Killed Their 2-Year-Old Boy

By MARCUS BARAM

May 2, 2008—

Two-year-old Ali Hussein is pulled

from the rubble of his family’s

home in the Shiite stronghold of

Sadr City in Baghdad, Iraq.

April 29, 2008

(Karim Kadim, AP Photo) Just like any other day, the Hussein family was getting ready for lunch at their home in Baghdad, Iraq, when the house suddenly shook and the brick walls came down around them.

That was the dramatic account told to ABC News by the parents of 2-year-old Ali Hussein, the Iraqi boy killed during a fierce battle in Sadr City Tuesday.

Dramatic photographs of Hussein’s dust-covered body being pulled out of the rubble of his home appeared on front pages and TV news reports around the world.

When a U.S. patrol in the Shiite militia stronghold was fired on by a dozen fighters, American forces fired 200-pound guided rockets that devastated at least three buildings in the district.

The U.S. military said 28 militiamen were killed. Local hospital officials said dozens of civilians were killed or wounded.

Hussein’s mother recounted being buried in rubble and crawling around the home, looking for her children.

“I was crying, ‘My children, my children.’ I saw the house destroyed. I did not know if they are alive or not.”

When Hussein’s father could not locate Ali, he said he began frantically digging.

“Everyone felt desperate and the police have left the scene, but I kept on digging. I told them I will not leave my son. I will take him out. I felt fainted after two hours of digging.”

The fire brigade arrived to help him find Ali and remove him from the house, according to Hussein’s father.

“They gave him to me, run to the ambulance, I hold his hand in the ambulance and it was cold. They made the first aid thing to the kid, open his eye, the rescuer looked at me, I told him you’re a believer, and accepts the results.”

Hussein’s father recalled how over the last month and a half the boy used to come to the main door of the house, wanting to go out and play.

“Ali was pushing against my legs and tell me, ‘Baba, Baba.’ He wanted to go out, and I did not let him out due to the military actions ongoing.”

“Ali was 2 years old, still future was in front of him. Ali, if he has an opinion, he would have said, ‘I do not want to interfere in the struggle.,”

The parents called on both Shiite militias and the U.S. military to stop operations in the violence-torn district. And they criticized American military efforts that resulted in the deaths of civilians.

“You attacked civilians’ houses crowded with people for the sake of a few militants,” said Hussein’s father, his face in tears. “A considerable number of people were killed for the sake of killing four.”

Although the parents did not mention it, they may qualify for condolence payments, which are made for death, injury or battle damage resulting from U.S. military operations. Such payments can range from $2,500 per incident to $10,000 per incident in extraordinary cases.

As of Thursday, the Multi-National Division in Baghdad has not decided whether to open an investigation into the “alleged noncombatant deaths,” which could result in condolence payments to Hussein’s family, according to an e-mail to ABC News’ Ryan Owens from LTC Steve Stover, spokesman with the 4th Infantry Division.

Copyright © 2008 ABC News Internet Ventures

Turkish Schools Offer Pakistan a Gentler Vision of Islam

By Sabrina Tavernise

New York Times / www.nytimes.com / , 2008

(Karachi, Pakistan)

Praying in Pakistan has not been easy for Mesut Kacmaz, a Muslim

teacher from Turkey.

He tried the mosque near his house, but it had Israeli and Danish flags

painted on the floor for people to step on. The mosque near where he

works warned him never to return wearing a tie. Pakistanis everywhere

assume he is not Muslim because he has no beard.

“Kill, fight, shoot,” Mr. Kacmaz said. “This is a misinterpretation of

Islam.”

But that view is common in Pakistan, a frontier land for the future of

Islam, where schools, nourished by Saudi and American money dating

back to the 1980s, have spread Islamic radicalism through the poorest

parts of society. With a literacy rate of just 50 percent and a public

school system near collapse, the country is particularly vulnerable.

Mr. Kacmaz (pronounced KATCH-maz) is part of a group of Turkish

educators who have come to this battleground with an entirely different

vision of Islam. Theirs is moderate and flexible, comfortably coexisting

with the West while remaining distinct from it. Like Muslim Peace

Corps volunteers, they promote this approach in schools, which are now

established in more than 80 countries, Muslim and Christian.

Their efforts are important in Pakistan, a nuclear power whose stability

and whose vulnerability to fundamentalism have become main

preoccupations of American foreign policy. Its tribal areas have become

a refuge to the Taliban and Al Qaeda, and the battle against

fundamentalism rests squarely on young people and the education they

get.

At present, that education is extremely weak. The poorest Pakistanis

cannot afford to send their children to public schools, which are free but

require fees for books and uniforms. Some choose to send their children

to madrasas, or religious schools, which, like aid organizations, offer

free food and clothing. Many simply teach, but some have radical

agendas. At the same time, a growing middle class is rejecting public

schools, which are chaotic and poorly financed, and choosing from a

new array of private schools.

The Turkish schools, which have expanded to seven cities in Pakistan

since the first one opened a decade ago, cannot transform the country on

their own. But they offer an alternative approach that could help reduce

the influence of Islamic extremists.

They prescribe a strong Western curriculum, with courses, taught in

English, from math and science to English literature and Shakespeare.

They do not teach religion beyond the one class in Islamic studies that is

required by the state. Unlike British-style private schools, however, they

encourage Islam in their dormitories, where teachers set examples in

lifestyle and prayer.

“Whatever the West has of science, let our kids have it,” said Erkam

Aytav, a Turk who works in the new schools. “But let our kids have their

religion as well.”

That approach appeals to parents in Pakistan, who want their children to

be capable of competing with the West without losing their identities to

it. Allahdad Niazi, a retired Urdu professor in Quetta, a frontier town

near the Afghan border, took his son out of an elite military school,

because it was too authoritarian and did not sufficiently encourage Islam,

and put him in the Turkish school, called PakTurk.

“Private schools can’t make our sons good Muslims,” Mr. Niazi said,

sitting on the floor in a Quetta house. “Religious schools can’t give them

modern education. PakTurk does both.”

The model is the brainchild of a Turkish Islamic scholar, Fethullah

Gulen. A preacher with millions of followers in Turkey, Mr. Gulen, 69,

comes from a tradition of Sufism, an introspective, mystical strain of

Islam. He has lived in exile in the United States since 2000, after getting

in trouble with secular Turkish officials.

Mr. Gulen’s idea, Mr. Aytav said, is that “without science, religion turns

to radicalism, and without religion, science is blind and brings the world

to danger.”

The schools are putting into practice a Turkish Sufi philosophy that took

its most modern form during the last century, after Mustafa Kemal

Ataturk, Turkey’s founder, crushed the Islamic caliphate in the 1920s.

Islamic thinkers responded by trying to bring Western science into the

faith they were trying to defend. In the 1950s, while Arab Islamic

intellectuals like Sayyid Qutub were firmly rejecting the West, Turkish

ones like Said Nursi were seeking ways to coexist with it.

In Karachi, a sprawling city that has had its own struggles with

radicalism — the American reporter Daniel Pearl was killed here, and

the famed Binori madrasa here is said to have sheltered Osama bin

Laden — the two approaches compete daily.

The Turkish school is in a poor neighborhood in the south of the city

where residents are mostly Pashtun, a strongly tribal ethnic group whose

poorer fringes have been among the most susceptible to radicalism. Mr.

Kacmaz, who became principal 10 months ago, ran into trouble almost

as soon as he began. The locals were suspicious of the Turks, who, with

their ties and clean-shaven faces, looked like math teachers from Middle

America.

“They asked me several times, ‘Are they Muslim? Do they pray? Are

they drinking at night?’ “ said Ali Showkat, a vice principal of the

school, who is Pakistani.

Goats nap by piles of rubbish near the school’s entrance, and Mr.

Kacmaz asked a local religious leader to help get people to stop throwing

their trash near the school, to no avail. Exasperated, he hung an Islamic

saying on the outer wall of the school: “Cleanliness is half of faith.”

When he prayed at a mosque, two young men followed him out and told

him not to return wearing a tie because it was un-Islamic.

“I said, ‘Show me a verse in the Koran where it was forbidden,’ “ Mr.

Kacmaz said, steering his car through tangled rush-hour traffic. The two

men were wearing glasses, and he told them that scripturally, there was

no difference between a tie and glasses.

“Behind their words there was no Hadith,” he said, referring to a set of

Islamic texts, “only misunderstanding.”

That misunderstanding, along with the radicalism that follows, stalks the

poorest parts of Quetta. Abdul Bari, a 31-year-old teacher of Islam from

a religious family, lives in a neighborhood without electricity or running

water. Two brothers from his tribe were killed on a suicide mission,

leaving their mother a beggar and angering Mr. Bari, who says a

Muslim’s first duty is to his mother and his family.

“Our nation has no patience,” said Mr. Bari, who raised his seven

younger siblings, after his father died suddenly a dozen years ago. He

decided that one of his brothers should be educated, and enrolled him in

the Turkish school.

The Turks put the focus on academics, which pleased Mr. Bari, who said

his dream was for Saadudeen, his brother, to lift the family out of

poverty and expand its horizons beyond religion. Mr. Bari’s title, hafiz,

means he has memorized the entire Koran, though he has no formal

education. Two other brothers have earned the same distinction. Their

father was an imam.

His is a lonely mission in a neighborhood where nearly all the residents

are illiterate and most disapprove of his choices, Mr. Bari said. He is

constantly on guard against extremism. He once punished Saadudeen for

flying kites with the wrong kind of boys. At the Turkish school, the

teenager is supervised around the clock in a dormitory.

“They are totally against extremism,” Mr. Bari said of the Turks. “They

are true Muslims. They will make my brother into a true Muslim. He’ll

deal with people with justice and wisdom. Not with impatience.”

Illiteracy is one of the roots of problems dogging the Muslim world, said

Matiullah Aail, a religious scholar in Quetta who graduated from Medina

University in Saudi Arabia.

In Baluchistan, Quetta’s sparsely populated province, the literacy rate is

less than 10 percent, said Tariq Baluch, a government official in the

Pasheen district. He estimated that about half of the district’s children

attended madrasas.

Mr. Aail said: “Doctors and lawyers have to show their degrees. But

when it comes to mullahs, no one asks them for their qualifications.

They don’t have knowledge, but they are influential.”

That leads to a skewed interpretation of Islam, even by those schooled in

it, according to Mr. Gulen and his followers.

“They’ve memorized the entire holy book, but they don’t understand its

meaning,” said Kamil Ture, a Turkish administrator.

Mr. Kacmaz chimed in: “How we interpret the Koran is totally

dependent on our education.”

In an interview in 2004, published in a book of his writings, Mr. Gulen

put it like this: “In the countries where Muslims live, some religious

leaders and immature Muslims have no other weapon in hand than their

fundamental interpretation of Islam. They use this to engage people in

struggles that serve their own purposes.”

Moderate as that sounds, some Turks say Mr. Gulen uses the schools to

advance his own political agenda. Murat Belge, a prominent Turkish

intellectual who has experience with the movement, said that Mr. Gulen

“sincerely believes that he has been chosen by God,” and described Mr.

Gulen’s followers as “Muslim Jesuits” who are preparing elites to run

the country.

Hakan Yavuz, a Turkish professor at the University of Utah who has had

extensive experience with the Gulen movement, offered a darker

assessment.

“The purpose here is very much power,” Mr. Yavuz said. “The model of

power is the Ottoman Empire and the idea that Turks should shape the

Muslim world.”

But while radical Islamists seek to re-establish a seventh-century Islamic

caliphate, without nations or borders, and more moderate Islamists, like

Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, use secular democracy to achieve the goal

of an Islamic state, Mr. Gulen is a nationalist who says he wants no more

than a secular democracy where citizens are free to worship, a claim

secular Turks find highly suspect.

Still, his schools are richly supported by Turkish businessmen. M. Ihsan

Kalkavan, a shipping magnate who has built hotels in Nigeria, helped

finance Gulen schools there, which he said had attracted the children of

the Nigerian elite.

“When we take our education experiment to other countries, we

introduce ourselves. We say, ‘See, we’re not terrorists.’ When people get

to know us, things change,” Mr. Kalkavan said in his office in Istanbul.

He estimated the number of Mr. Gulen’s followers in Turkey at three

million to five million. The network itself does not provide estimates,

and Mr. Gulen declined to be interviewed.

The schools, which also operate in Christian countries like Russia, are

not for Muslims alone, and one of their stated aims is to promote

interfaith understanding. Mr. Gulen met the previous pope, as well as

Jewish and Orthodox Christian leaders, and teachers in the schools say

they stress multiculturalism and universal values.

“We are all humans,” said Mr. Kacmaz, the principal. “In Islam, every

human being is very important.”

Pakistani society is changing fast, and more Pakistanis are realizing the

importance of education, in part because they have more to lose, parents

said. Abrar Awan, whose son is attending the Turkish school in Quetta,

said he had grown tired of the attitude of the Islamic political parties he

belonged to as a student. Now a government employee with a steady job,

he sees real life as more complicated than black-and-white ideology.

“America or the West was always behind every fault, every problem,” he

said, at a gathering of fathers in April. “Now, in my practical life, I know

the faults are within us.”

An Open Letter to His Eminence Francis Cardinal George, OMI,

Archbishop of Chicago, P.O. Box 1979,Chicago, IL 60690–1979

by Bob Waldrop, Oscar Romero Catholic Worker House, www.justpeace.org

March 26, 2008

Dear Cardinal George:

I have read the news reports and the Archdiocesan statement concerning the disruption of an Easter mass that you celebrated at your Cathedral. Your official statement says, in part. . . “This is a profoundly disturbing action. . . It is a sacrilege that should be condemned by all people of faith and good will.”

Although I actively oppose the unjust war the United States is waging on the people of Iraq, I agree that the demonstrators action was disturbing and sacrilegious.

However, theirs was not the first sacrilegious act of that day. The sacrilege commenced when you ascended to the Altar of God and began to celebrate the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass with your hands dripping with the blood of the innocent in Iraq whom you and most of the other United States Catholic Bishops have so callously abandoned to their grisly and violent fates. Like the rest of the US Bishops save one, you issued no canonical declaration forbidding Catholics of the Archdiocese of Chicago from participation in the unjust war on the people of Iraq. A review of your website finds no pastoral letter instructing the souls entrusted to your care about the Church’s teachings on unjust war and condemning the war on the people of Iraq as unjust. Like nearly all of your confreres in the U.S. hierarchy, you have preached a gospel of moral relativism and moral laxism that makes a mockery of the Church’s teachings on life. You claim you want “peace”, but you have done nothing to actually support peace other than to offer pious platitudes and hypocritical rhetoric from your position of safety in your palatial Chicago residence.

Your holidays and festivals I detest, they weigh me down, I tire of the load. When you spread out your hands, I close my eyes to you; though you pray the more, I will not listen. Your hands are full of blood! Wash yourselves clean! Put away your misdeeds before my eyes; cease doing evil, learn to do good. Make justice your aim, redress the wronged, hear the orphan’s plea, defend the widow. Isaiah 1

I am obviously just an obscure Catholic Worker. You and all the other bishops have consistently ignored everything I have had to say to you since I started writing bishops on the Feast of the Holy Innocents in 2001. Which is fine with me, I am not interested in collecting letters of denial from bishops and cardinals making excuses for their moral cowardice. The charism of the Catholic Worker movement is faithfulness to the Gospel of Justice and Peace - even when all of the United States bishops save a small handful choose Nationalism over Catholicism. So once more I write again these words of inconvenient faithfulness, to remind you that God is watching every moment of your reign as Archbishop and Cardinal and you will one day be accountable for these actions.

God was watching when you refused to properly catechize your people about unjust war.

God was watching when you refused to forbid Chicago Catholics from participating in an unjust war.

God was watching when you dined with the Tyrant-Emperor George Bush, and you did not condemn him as a murderer and prosecutor of an unjust war.

A reading from the book of the Prophet Micah. . .

“And I said, Listen you leaders of Jacob, house of Israel! Is it not your duty to know what is right, you who hate what is good, and love evil? You who tear their skin from them and their flesh from their bones? They eat the flesh of my people and flay their skin from them, and break their bones. They chop them in pieces like flesh in a kettle, and like meat in a caldron. When they cry to the Lord, he shall not answer them, rather shall God hide from them at that time, because of the evil they have done.

Thus says the LORD regarding the prophets who lead my people astray; Who, when their teeth have something to bite, announce peace, But when one fails to put something in their mouth, proclaim war against him.

Therefore you shall have night, not vision, darkness, not divination; The sun shall go down upon the prophets, and the day shall be dark for them.

Then shall the seers be put to shame, and the diviners confounded; They shall cover their lips, all of them, because there is no answer from God. . . .

Therefore, because of you, Zion shall be plowed like a field, and Jerusalem reduced to rubble, And the mount of the temple to a forest ridge.”

So as it turns out, when you condemn these young people, you condemn yourself.

Which is worse? A prince of the church who by any objective judgment is a moral coward who has preached a false gospel of moral laxism and relativism regarding an unjust war? Or a few young people, who hear the cries of the victims, and in despair act out in such a public manner? Is it not true that your own abject failure as a Cardinal Archbishop provoked these young people to such a rash action? Are you not, then, a “secondary disrupter” of your own Mass, and thus have a significant share in the responsibility for their deeds? Have not your actions — or rather, inactions — violated the inalienable rights of the people of Iraq to life? Who, then, is really at fault in this matter? These young protestors? Or a cowardly Cardinal Archbishop, who shuts his eyes, ears, and heart to the cries of the people of Iraq for justice and peace and is a scandal before the entire world?

I write these words to you, in remembrance of the hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians and soldiers who have died in this unjust war on the people of Iraq. One day you will meet them and they will tell you of their terror, pain, and fear and they will ask you, “Why, in the name of God, did you not do something serious to stop this from happening?”

I pray that God has mercy on your soul and brings you to an understanding of the grave evil and moral disorders that you and the other United States Catholic Bishops foster and encourage by your moral cowardice in the face of this unjust war on the people of Iraq

Sincerely,

/sig/

Bob Waldrop

Oscar Romero Catholic Worker House

1524 NW 21st

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73106

www.justpeace.org

Counting Iraqi Casualties & a Media Controversy

by John Tirman Editor & Publisher / February 14, 2008

EditorAndPublisher.com

One puzzling aspect of the news media’s coverage of the Iraq war is their squeamish treatment of Iraqi casualties. The scale of fatalities and wounded is a difficult number to calculate, but its importance should be obvious. Yet, apart from some rare and sporadic attention to mortality figures, the topic is virtually absent from the airwaves and news pages of America. This absence leaves the field to gross misunderstandings, ideological agendas,and political vendettas.

The upshot is that the American public—and U.S. policy makers, for that matter—are badly informed on a vital dimension of the war effort. As an academic interested in the war’s violence, I commissioned a household survey in October 2005 to gauge mortality, and I naturally turned to the best professionals available—the Johns Hopkins University epidemiologists who had conducted such surveys before in Iraq, Congo, and elsewhere. Their survey of 1,850 households resulted in a shocking number: 600,000 dead by violence in the first 40 months of the war. The survey was extensively peer reviewed and published in the British medical journal, the Lancet, in October 2006.

The findings caused a ripple of interest (in part because President Bush, during a press conference, called the results “not credible”) and stirred a very lively debate among the few people interested in the methods. By and large, however, the survey passed from public view fairly quickly, and the news media continued to cite the very low numbers produced by the Iraq Body Count, a U.K.-based NGO that counts civilian deaths through English-language newspaper reports.

Another survey, this one undertaken by a private U.K. firm, Opinion Business Research (ORB), found more than one million dead through August 2007. Yet another, a much larger house-to-house survey was conducted by the Iraq Ministry of Health (MoH). This also found a sizable mortality figure—400,000 “excess deaths” (the number above the pre-war death rate), but estimated 151,000 killed by violence. The period covered was the same as the survey published in The Lancet, but was not released until January 2008.

The ORB results were almost totally ignored in the American press, and the MoH numbers, which did get one-day play, were covered incompletely. Virtually no newspaper report dug into the data tables of the Iraqi MoH report, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, for that total excess mortality figure, or to ask why the MoH report showed a flat rate for killing throughout the war when every other account shows sharp increases through 2005 and 2006. The logical explanation for this discrepancy is that people responding to interviewers from the government, and a ministry controlled by Moktada al Sadr, would not want to admit that their loved one died by violence. There were, instead, very large numbers of dead by road accidents and “unintentional injuries.” The American press completely missed this.

What some in the news media did not miss, however, was a full-scale assault on the legitimacy of the Lancet article by the National Journal, the “insider” Capitol Hill weekly.

The attack, by reporters Carl Cannon and Neil Munro, which was largely built on persistent complaints of two critics and heaps of innuendo, was largely ignored—its circulation is only about 10,000—until the Wall Street Journal picked up on one bit of their litany: that “George Soros” funded the survey. “The Lancet study was funded by anti-Bush partisans and conducted by antiwar activists posing as objective researchers,” said the January 9, 2008, editorial (titled “The Lancet’s Political Hit”) and concluded: “the Lancet study could hardly be more unreliable.” The editorial created sensation in the right-wing blogosphere and in several allied news outlets.

Let me convey what I thought was a simple and unremarkable fact I told Munro in an interview in November and one of the Lancet authors emailed Cannon the details of how the survey was funded. My center at MIT used internal funds to underwrite the survey. More than six months after the survey was commissioned, the Open Society Institute, the charitable foundation begun by Soros, provided a grant to support public education efforts of the issue. We used that to pay for some travel for lectures, a web site, and so on. OSI, much less Soros himself (who likely was not even aware of this small grant), had nothing to do with the origination, conduct, or results of the survey. The researchers and authors did not know OSI, among other donors,had contributed. And we had hoped the survey’s findings would appear earlier in the year but were impeded by the violence in Iraq. All of this was told repeatedly to Munro and Cannon, but they choose to falsify the story. Charges of political timing were especially ludicrous, because we started more than a year before the 2006 election and tried to do the survey as quickly as possible. It was published when the data were ready.

The New York Post and the Sunday Times of London, both owned by Rupert Murdoch, followed the WSJ editorial and trumpeted the Soros connection and the supposed “fraud” which Munro and Cannon hinted. “$OROS IRAQ DEATH STORY WAS A SHAM” was a headline in the Post, which was followed by a story in which scarcely anything stated was true.

The charges of “fraud” that were also central to the National Journal piece ere based on distortions or ignorance of statistical method, such as random sampling and sample size, or speculations about Iraqi field researchers fabricating data. Nothing close to proof of misdeeds was ever offered.The two principal authors, Gilbert Burnham and Les Roberts, parried the fraud charges effectively on their web site and in letters to the editors,but of course these are rarely noticed as much as the original charges. Those charges were wholly speculative and at times based on small irregularities in the collection of data, hardly a crime in the midst of the bloodiest period of the war. For example, some death certificates were not collected from respondents; about 80 percent of the time they were. (In the Iraqi MoH survey, death certificates were never collected, making their claims about violence v. nonviolent causes unconfirmable.)

In any case, the many peer reviews of The Lancet article, including one by a special committee of the World Health Organization, gave the survey methods and operations passing grades.

Munro then went on the Glenn Beck program and suggested the Iraqi researchers were

unreliable (“without U.S. supervision”) and that the Lancet authors “made it clear they wanted this study published before the election.” Both of those assertions are untrue. Beck then repeated these allegations on his radio program, and added that there was no peer review of the fatality figures, another falsehood, and “we’re getting it jammed down our throat by people who are undercover who are pulling purse strings, who are manipulating the news.”

The charge, repeated in all these media, that the Iraqi research leader, Riyadh Lafta, M.D., operated “without U.S. supervision” and was therefore suspect is particularly interesting. Munro, in a note to National Review Online, asserted that Lafta “said Allah guided the prior 2004 Lancet/Johns Hopkins death-survey,” which he also had noted in the National Journal piece. When he interviewed me he pestered me about two anonymous donors,demanding to know if either were Arab or Muslim. A pattern here is visible, one which reeks of religious prejudice.

Munro had also ignored the corroborating evidence I sent him, the 4.5 million displaced (suggesting hundreds of thousands of fatalities, drawing on the ratio of all other wars); estimates of new

widows (500,000 from the war); and the other surveys done in Iraq suggesting enormous numbers of casualties (ABC/USA Today poll of March 2007, showing roughly 53% physically harmed by war). When I mentioned these things to him on the telephone, he literally screamed that such data didn’t matter, that the Lancet probe was “a hoax.” Lancet article authors also cite several cases where they were misquoted. The National Journal’s editors have been informed of their reporters’ misconduct and errors, and have not responded.

So the smear is complete—a “political hit” by the “anti-Bush billionaire,” complicity by anti-war academics, fraud by Muslims devoted to Allah—and repeated over and over in the right-wing media. Little has of this has appeared in the legitimate news media, apart from right-wing columnists like Jeff Jacoby in the Boston Globe.

One might expect that such nonsense is obvious to neutral observers, but it constitutes a kind of harassment that scholars must fend off, diverting from more important work. Gilbert Burnham, the lead author on the Lancet article, runs health clinics in Afghanistan and East Africa, and is spending inordinate amounts of time responding to the attacks. Les Roberts, a coauthor, and I have both had colleagues at our universities called by Munro to ask if they would punish us for fraud. The OSI people have also been writing letters to set the record straight. Most important, Riyadh Lafta, who has been threatened before, may be in more danger due to these attacks.

As to the issue of the human cost of the war, even the legitimate press that has avoided this kerfuffle might be intimidated from taking on the issue in depth. The fact that the National Journal hatchet job and the MoH surveym appeared within days of each other sent a message to editors around the United States—one survey is “discredited” and one is legitimate. The treatment of the MoH survey that week often noted its death-by-violence number was one-fourth of the Lancet figure — forgetting, again, that total war-related mortality were much closer in both, and congruent with other surveys. The New York Times did run an editorial in early February about the dead in Iraq — the 124 journalists killed in the war. The topic of the war’s exceptional human costs, now inflamed by these calumnies, appears to be too hot to handle. Even with all this fuss in January, no explorations of the Iraqi mortality from the war have appeared in the major dailies. No editorials, no examination of the methods (or the

danger and difficulty of collecting data), no sense that the scale of killing might affect the American position, or might shed some light on U.S.war strategy, or might point to honorable exits and reconstruction obligations. Remarkably, no curiosity at all about the dead of Iraq, and what they can tell us. That, in the end, may be the biggest injustice of all.

The following article on my friend Gordon Zahn struck me as timely because of our current campaign at Marquette, a Jesuit University and the Jesuit opposition to Gordon’s (at the time a professor at Loyola, a Jesuit univesity in Chicago) publication of his first book “Catholic Germans and Hitler’s War.”

A Man of Peace: Gordon C. Zahn, 1918–2007

by Michael W. Hovey

Commonweal /www.commonwealmagazine.org / February 15, 2008

On the night of John Leary’s funeral in Boston in August 1982, I ran into Gordon Zahn in Copley Square. His face was lined with tears. Young Leary, a Catholic pacifist and Harvard grad, had dropped dead

a few days before while jogging along the Charles River. He was twenty-four years old.

“I’m Mike Hovey,” I said, sensing Professor Zahn didn’t recognize me. “I lived with John at Haley House [the Boston Catholic Worker].” “Oh yes,” Gordon responded. “Have you eaten yet?” Then he invited

me for a drink and a bite. “I need some company,” he said. It was the beginning of a long friendship.

Gordon died at the age of eighty-nine on December 9, 2007, from complications related to Alzheimer’s disease. He never cut an imposing figure. He dressed like a college professor, which he was, and his demeanor was modest and never overbearing. A hearing impairment that began in his mid-twenties made him strain to follow what others were saying, especially in groups. But whatever he lacked in physical stature, his moral consistency and personal courage made people pay attention.

His many contributions to the Catholic Church on issues of conscience and war, peace, and social justice will long outlive him. His writings as a Catholic “public intellectual”-for an audience both in and outside the academy-and his leadership in various peace organizations (he was a cofounder of Pax Christi USA) began early on. He was a conscientious objector during World War II. A letter he wrote at the time seeking support for his position from his archbishop in Milwaukee was never answered. That experience helped shape Zahn’s life mission, which was to draw attention to the church’s failure to

“speak truth to power” and to constructively engage leaders and the faithful in rediscovering the pacifist roots of early Christianity.

After the war, Gordon took a doctorate in sociology and began an academic career. He never married. As a faculty member at Loyola University Chicago, he wrote his first book, German Catholics and Hitler’s Wars. In it he explored the role of the German Catholic hierarchy in Nazi Germany and how it generally counseled “prudence,” if not wholesale capitulation, in dealing with the authorities. Jesuit and Vatican officials alike tried to suppress publication of the book, but failed. While researching the topic on a Fulbright scholarship, Gordon discovered the story of a young Austrian farmer, Franz Jägerstätter, who refused to serve in the Nazi army and was beheaded for his conscientious objection in Berlin on August 9, 1943. Jägerstätter went to his death without the support of his pastor or his bishop, and he left behind a wife and four daughters.

Gordon’s In Solitary Witness: The Life and Death of Franz Jägerstätter was published in 1964. The following year, Archbishop Thomas Roberts, SJ, of Bombay, drew attention to Jäegerstätter’s

example in a speech at Vatican II. That speech, together with lobbying by Gordon and other Catholic pacifists (among them Dorothy Day,Eileen Egan, and James Douglass) led the council to include support

for conscientious objection to war in Gaudium et spes-a significant change in Catholic teaching.

As Jägerstätter’s story became more widely known, thanks initially to Gordon’s book, growing numbers of people from around the world began to gather annually at Franz’s grave. Eventually, the church in

Austria opened the process for promoting his canonization. This past October, a major stage in that process was reached in Linz, Austria, when Jägerstätter was declared “Blessed,” a martyr for the faith. His daughters and his ninety-four-year-old widow, Franziska, were joined by more than five thousand others at the Mass of beatification. Unfortunately, Gordon was not able to attend because of his declining health.

In the 1980s, Zahn became a key consultant to the U.S. bishops’committee charged with drafting the pastoral letter, The Challenge of Peace: God’s Promise and Our Response. Again, history was made

when the bishops wrote that pacifism and a commitment to Christian nonviolence are fully consonant with gospel principles, and thus legitimate positions for Catholics to take regarding war. Gordon’s

writings proved seminal in this declaration.

Gordon wrote several other books, including one on his experience in the Civilian Public Service during World War II, and another on British Royal Air Force chaplains. He also edited a collection of

Thomas Merton’s essays on war and violence. From 1950 to 1999, he wrote more than thirty articles and reviews for Commonweal, usually on issues related to peacemaking, but also on other disputed topics like the civil rights of homosexuals (which he defended), and women presiders at the Eucharist at the Milwaukee Catholic Worker house (which he opposed).

After retiring from teaching at the University of Massachusetts-Boston in 1982, Gordon ended his career as national director of the Pax Christi USA Center on Conscience and War in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where I served as executive director. I learned much while seated at the master’s feet, including the importance of ending the day with a decent martini! May he rest in peace.

Testimony of a US ex-marine

By Rosa Miriam Elizalde

from Information Clearinghouse

31/01/08 “ACN” — -- “I’m 32 and I am a trained psychopathic murderer. The only things I can do are to sell youths the idea of joining the marines and kill. I am not able to keep a job. For me civilians are despicable people, mentally retarded and weak persons, a flock of sheep. I am their sheepdog. I am a predator. In the army they used to call me Jimmy, the Shark”.

That was part of the second chapter of the book Jimmy wrote three years ago, with the assistance of journalist Natasha Saulnier, and which was launched at the 2007 Caracas Book Fair. Cowboys of Hell is the most violent testimony that has been written thus far based on the experience of a former member of the Marine Corps, one of the first to arrive in Iraq during the 2003 invasion. A is determined to tell, as many times as necessary, what having been a merciless marine for twelve years meant to him and why the Iraq war changed him.

Jimmy participated as a panelist at the fair’s main workshop, which had a controversial title: “The United States, the Possible Revolution” and his testimony possibly had the strongest expected impact on the audience. He has his hair cut in the military style and wears sun glasses; he walks with martial air and he has his arms covered with tattoos. He looks just like what he used to be: a marine. But when he speaks he looks different: he is someone marked by a horrifying experience from which he tries to keep other unwary youths away. As he assures in his book, he has not been the only one to have killed people in Iraq; that was a permanent practice by his fellow men. Four years after having abandoned the war, he still feels he is being chased by his nightmares.

Q What do all those tattoos mean?

A I’ve got a lot of them. I was tattooed in the military. Here in my hand (he shows his thumb and his ring finger), you can see the Blackwater logo, the mercenary army founded where I was born, there in North Carolina. I had this one done in an act of resistance because marines are not allowed to tattoo the area between their wrists and their hands. One day the members of my platoon got drunk and we all had the same tattoo done: a cowboy with bloodshot eyes over several aces, representing death. It means exactly what is going on: “you killed somebody. “ On the right arm is the marines’ logo with the flags of the United States and Texas, where I joined the US armed forces. On my chest, here on the left side there is a Chinese dragon ripping the skin and which means that pain is our weakness leaving our body. What kills us makes us stronger.

Q Why did you say that you had met the worse people ever in your life in the US Marines?

A The United States only has two ways of using the marines: to undertake humanitarian missions and to kill. Over the 12 years I was with them, I never took part in humanitarian missions.

Q Before you went to Iraq you recruited youths for the marines. Can you describe a recruiting officer in the United States?

A A liar. The Bush administration has forced the US youths to join the armed forces and what the government basically does –and I did too—is trying to get people through economic incentives. During three years I recruited 74 youths who never told me that they wanted to join the armed forces because they wanted to defend their country or due to any patriotic reason. They wanted to get money to go to university or get a health insurance. So, I would first tell them about all those advantages and only in the end I would tell them that they will serve our homeland. I never happened to recruit the son of a rich person. In order to keep our job, we as recruiting officers, could not think of any scruples.

Q I understand that the Pentagon has been less demanding as to the requisites to join the army. What does that mean?

A recruiting standards have enormously been eased, because almost nobody wants to join in. Having mental problems or a criminal record is no longer a problem. Persons that have committed felonies can join the army; that include those who have been given over-one-year sentences, which is considered a serious crime. Also accepted are youths who have not concluded high school studies; if they pass the psychological test, they can join the army.

Q You changed after the war, but could you tell me about your feelings before that?

A I felt just like the other soldiers who believed what they were told. However, since I began my recruiting work I felt bad about it: as a recruiting officer I had to tell lies all the time.

Q But, you believed that your country was involved in a fair war against Iraq.

A Yes, Intelligence reports we received read that Saddan had weapons of mass destruction. Later, we found out that everything was a lie.

Q When did you find out you had been deceived?

A Once in Iraq, where I arrived in March 2003. My platoon was ordered to go to the places formerly controlled by the Iraqi army and we saw thousands of thousands of ammunitions in boxes bearing the US label; they were there since the US had supported the Saddan government against Iran. I saw some boxes with the US flag on them and I even saw American tanks. My marines—I was a sergeant with E-6 category, a staff sergeant, which is a higher rank and I had 45 marines under my command— would ask me why there were US ammunitions in Iraq. They couldn’t understand it. CIA reports said that the Salmon Pac was a terrorist camp and that we would find chemical and biological weapons there, but we found nothing. In that moment I began to think that our real mission in Iraq was focused on oil.

Q The most disturbing lines in your book are those in which you describe yourself as a psychopathic murderer. Could you explain why you said that?

A I was a psychopathic murderer because I was trained to kill. I was not born with that mentality. It was the Marines that trained me to be a gangster in the interest of US corporations, a criminal. They trained me to fulfill, without thinking, the orders of the President of the United States and bring him what he asked for, without any moral consideration. I was a psychopath because we were trained to shoot first and ask later, as an insane person would act, not a professional soldier that is to face another soldier. If we had to kill women and children, we would do it; therefore, we were not soldiers, we were mercenaries.

Q What specific experience of yours made you reach that conclusion?

A Well, there were some of them. Our mission was to go to different cities and guarantee security in the roads. There was an accident in particular—and many others as well—which really put me in a serious situation. It was about a car with Iraqi civilians. All intelligence reports said that those cars had bombs and explosives on board. That was the information that we received. When those cars approached our areas we made warning shots; when they did not slow down to the speed we indicated, we would shoot at them without ceremony.

Q You shot at them with your machineguns?

A Yes, We expected to see explosions every time we riddle the cars with bullets; but we never heard or see an explosion. Then we opened the car and all we found was people killed or wounded, not a single weapon, not a single Al Qaeda propaganda, nothing. We only found civilians in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Q In your book, you also described how your platoon machine-gunned peaceful demonstrators. Is that right?

A Right. In the surroundings of the Rasheed Military Complex, South of Baghdad and near the Tigris River, there was a group of people staging a demonstration, right at the end of the street. They were youths; they had no weapons. So, when we advanced, we saw a tank parked on one side of the street, the driver told us that they were peaceful demonstrators. If those Iraqi people had had any violent intentions, they would have blown up the tank; but they did not. They were only staging a demonstration. That calmed us down because we thought that “if they were there to shoot at us, they had already had enough time to do so. “ They were standing about 200 meters from our patrol.

Q Who gave the order to shoot at the demonstrators?

We were told by the high command to keep watching those civilians, because many combatants with the Republican Forces had taken off their uniforms and were wearing civilian clothes to undertake terrorist attacks against US soldiers. The intelligence reports we received were known basically by every member in the commanding chain. All marines were well aware about the structure of the commanding chain that was set up in Iraq. I think that the order to shoot at the demonstrators came from high-rank US administration officers, which included both military intelligence agencies and governmental circles.

Q And what did you do?

A I returned to my vehicle, my Humvee (a highly equipped jeep) and I heard the sound of a shot over my head. My marines started shooting, so did I. We were not shot back, and I had already shot 12 times. I wanted to make sure that we had killed people according to combat requirements set by the Geneva Convention and the operational proceedings established in the rules. I tried not to look at their faces, I only looked for weapons, but I found none.

Q How did your superior officers react at that?

A They told me that “shit happens. “

Q And when your marines found out that they had been deceived, what was their reaction?

A I was second in command. My marines asked me why we were killing so many civilians. “ Can you talk to the lieutenant? “, the answer was “No”. But when they found out that it all was a lie, they were really mad.

Our first mission in Iraq was not aimed at offering humanitarian assistance, as the media said, but to secure oil fields in Bassora. In the city of Karbala, we used our artillery during 24 hours; it was the first city we attacked. I thought we were there to give the population food and medical assistance. Negative. We kept on advancing towards the oil fields.

Before arriving in Iraq we went to Kuwait. We got there in January 2003 with our vehicles loaded with food and medicines. I asked the lieutenant what we were going to do with all those supplies, since we had little room for us with so much stuff. He told me that his captain had ordered him to download everything in Kuwait. Shortly after that, we were ordered to burn everything, all the food and the medical supplies.

Q You have also denounced the use of depleted uranium…

A I am 35 years old and I only have 80 percent of my lung capacity left. I have been diagnosed a degenerative disease in my backbone, chronic fatigue and pains in my tendons. You know, I used to run 10 kilometers just because I liked to run, and now I can only walk between 5 and 6 kilometers every day. I am afraid of having children because of that. I got a swollen face. Look at this picture (He shows me the photo on his Book Fair credential). This photo was taken shortly after I returned from Iraq. I look like Frankenstein. I owe all that to depleted uranium, now you can imagine what is happening to the people in Iraq.

Q And what happened when you returned to the United States?

A They treated me as if I were crazy, as if I were a coward, a traitor.

Q Your superior officers have said that all you have revealed is a lie.

A There is overwhelming evidence against them. The US armed forces are finished. The longer the war, the bigger chance for my truth to be known.

Q The book you have presented in Venezuela has been published in Spanish and French. Why haven’t you published it in the United States?

A The publishing houses have requested the elimination of real names of the people involved and the presentation of the war in Iraq in sort of a mist that makes it less crude, and I am not willing to do that. Publishing houses like New Press, an alleged left wing entity, refused to publish the book because they fear to be involved in a dispute raised by the people described in the story.

Q Why some media outlets like The New York Times and The Washington Post never reproduced your testimony?

A I never echoed the official version of the facts, which says that US troops were in Iraq to help the people; I never repeated their story that civilians there died in accidents. I refused to say that. I did not see any accidental shooting against the Iraqi and I refused to lie.

Q Have you changed that stance?

A No. What they have done is to add opinions and books by people with conscious objections: those who are against the war in general or those who participated in the war but who did not have this kind of experience. They are still reluctant to look straight to reality.

Q Do you have any photos or documents that may prove what you have told us?

A No, I don’t. They stripped me of all my belongings when I was ordered to return to the United States. I returned home only with two weapons: my mind and a knife.

Q Do you think there is a short-time solution to the war?

A No, I don’t think so. What I see is the same policy being practiced either by democrats or republicans. They are the same thing. The war is a business for both parties, since they depend on the Military Industrial Complex. We need a third party.

Q Which one?

A the party of Socialism.

Q You have participated in a workshop titled “The United States: The Revolution is Possible. “ Do you really think that a revolution could take place in the United States?

A It has already begun to take place in the South, where I was born.

Q But southern United States has traditionally been the most conservative zone in your country.

That changed after Katrina. New Orleans looks like Baghdad. The people in the South are indignant and they wonder every day how comes that Washington invests in a useless war and in Baghdad, while it has not invested in New Orleans. You must recall that the first big rebellion in the United States started in the South.

Q Would you be willing to visit Cuba?

A I admire Fidel and the Cuban people, and if I am invited to visit, for sure I would. I do not mind what my government might say to me. Nobody will control me.

Q Do you know that the symbol of US imperial despise against our nation is precisely a photo depicting some marines as they urinated on the statue of Jose Marti, who is the Cuban National Independence Hero?

A Yes, I do. In the Marine Corps they spoke of Cuba as a US colony and they taught us some history. As part of his training, a marine must learn facts about the countries he is expected to invade, as the song goes.

Q What song, the marines´ song?

A (singing) “ From the halls of Montezuma, to the shores of Tripoli…”

Q That means that the marines want to be in all parts of the world?

A Their dream is to control the world…, no matter if in that effort we all are turned into murderers

What’s your consumption factor?

By Jared Diamond The New York Times

Wednesday, January 2, 2008

To mathematicians, 32 is an interesting number: It’s 2 raised to the fifth power, 2 times 2 times 2 times 2 times 2. To economists, 32 is even more special, because it measures the difference in lifestyles between the first world and the developing world. The average rates at which people consume resources like oil and metals, and produce wastes like plastics and greenhouse gases, are about 32 times higher in North America, Western Europe, Japan and Australia than they are in the developing world. That factor of 32 has big consequences. To understand them, consider our concern with world population.

Today, there are more than 6.5 billion people, and that number may grow to around 9 billion within this half-century. Several decades ago, many people considered rising population to be the main challenge facing humanity. Now we realize that it matters only insofar as people consume and produce. If most of the world’s 6.5 billion people were in cold storage and not metabolizing or consuming, they would create no resource problem. What really matters is total world consumption, the sum of all local consumptions, which is the product of local population times the local per capita consumption rate.

The estimated 1 billion people who live in developed countries have a relative per capita consumption rate of 32. Most of the world’s other 5.5 billion people constitute the developing world, with relative

per-capita consumption rates below 32, mostly down toward 1 .The population especially of the developing world is growing, and some people remain fixated on this. They note that populations of countries like Kenya are growing rapidly, and they say that’s a big problem.

Yes, it is a problem for Kenya’s more than 30 million people, but it’s not a burden on the whole world, because Kenyans consume so little. (Their relative per capita rate is 1.) A real problem for the world is that each of the 300 million Americans consumes as much as 32 Kenyans. With 10 times the population, the United States consumes 320 times more resources than Kenya does.

People in the third world are aware of this difference in per capita consumption, although most of them couldn’t specify that it’s by a factor of 32. When they believe their chances of catching up to be hopeless, they sometimes get frustrated and angry, and some become terrorists, or tolerate or support terrorists. Since Sept. 11, 2001, it has become clear that the oceans that once protected the United States no longer do so. There will be more terrorist attacks against us and Europe, and perhaps against Japan and Australia, as long as that factorial difference of 32 in consumption rates persists.

People who consume little want to enjoy the high-consumption lifestyle. Governments of developing countries make an increase in living standards a primary goal of national policy. And tens of millions of people in the developing world seek the first-world lifestyle on their own, by emigrating, especially to the United States and Western Europe, Japan and Australia. Each such transfer of a person to a high-consumption country raises world consumption rates, even though most immigrants don’t succeed immediately in multiplying their consumption by 32.

Among the developing countries that are seeking to increase per capita consumption rates at home, China stands out. It has the world’s fastest growing economy, and there are 1.3 billion Chinese, four times the United States population. The world is already running out of resources, and it will do so even sooner if China achieves American-level consumption rates. Already, China is competing with us for oil and metals on world markets.

Per capita consumption rates in China are still about 11 times below ours, but let’s suppose they rise to our level. Let’s also make things easy by imagining that nothing else happens to increase world consumption - that is, no other country increases its consumption, all national populations (including China’s) remain unchanged and immigration ceases. China’s catching up alone would roughly double world consumption rates. Oil consumption would increase by 106 percent, for instance, and world

metal consumption by 94 percent.

If India as well as China were to catch up, world consumption rates would triple. If the whole developing world were suddenly to catch up, world rates would increase eleven-fold. It would be as if the world population ballooned to 72 billion people (retaining present consumption rates).

Some optimists claim that we could support a world with nine billion people. But I haven’t met anyone crazy enough to claim that we could support 72 billion. Yet we often promise developing countries that if they will only adopt good policies - for example, institute honest government and a free-market economy - they too will be able to enjoy a first-world lifestyle. This promise is impossible, a cruel hoax: we are having difficulty supporting a first-world lifestyle even now for only 1 billion people.

Americans may think of China’s growing consumption as a problem. But the Chinese are only reaching for the consumption rate Americans already have. To tell them not to try would be futile. The only approach that China and other developing countries will accept is to aim to make consumption rates and living standards more equal around the world. But the world doesn’t have enough resources to allow

for raising China’s consumption rates, let alone those of the rest of the world, to our levels. Does this mean we’re headed for disaster? No, we could have a stable outcome in which all countries converge on consumption rates considerably below the current highest levels. Americans might object: There is no way we would sacrifice our living standards for the benefit of people in the rest of the world Nevertheless, whether we get there willingly or not, we shall soon have lower consumption rates, because our present rates are unsustainable.

Real sacrifice wouldn’t be required, however, because living standards are not tightly coupled to consumption rates. Much American consumption is wasteful and contributes little or nothing to quality of life. For example, per capita oil consumption in Western Europe is about half of ours, yet Western Europe’s standard of living is higher by any reasonable criterion, including life expectancy, health, infant mortality, access to medical care, financial security after retirement, vacation time, quality of public schools and support for the arts. Ask yourself whether Americans’ wasteful use of gasoline contributes positively to any of those measures.

Other aspects of our consumption are wasteful, too. Most of the world’s fisheries are still operated non-sustainably, and many have already collapsed or fallen to low yields - even though we know how to manage them in such a way as to preserve the environment and the fish supply. If we were to operate all fisheries sustainably, we could extract fish from the oceans at maximum historical rates and carry on indefinitely.

The same is true of forests: We already know how to log them sustainably, and if we did so worldwide, we could extract enough timber to meet the world’s wood and paper needs. Yet most forests are managed

non-sustainably, with decreasing yields.

Just as it is certain that within most of our lifetimes we’ll be consuming less than we do now, it is also certain that per capita consumption rates in many developing countries will one day be more nearly equal to ours. These are desirable trends, not horrible prospects. In fact, we already know how to encourage the trends; the main thing lacking has been political will.

Fortunately, in the last year there have been encouraging signs. Australia held a recent election in which a large majority of voters reversed the head-in-the-sand political course their government had

followed for a decade; the new government immediately supported the Kyoto Protocol on cutting greenhouse gas emissions. Also in the last year, concern about climate change has increased

greatly in the United States. Even in China, vigorous arguments about environmental policy are taking place, and public protests recently halted construction of a huge chemical plant near the center of Xiamen. Hence I am cautiously optimistic. The world has serious consumption problems, but we can solve them if we choose to do so.

Jared Diamond, a professor of geography at the University of

California, Los Angeles, is the author of “Collapse” and “Guns, Germs and

Steel.”

http://www.iht.com/articles/2008/01/02/opinion/ediamond.php

At Christmas, Iraqi Christians Ask for Forgiveness, and for Peace

New York Times / www.nytimes.com / December 25, 2007

By Damien Cave